Beware of the audience

A letter to Magnus Midtbø

Hi Magnus,

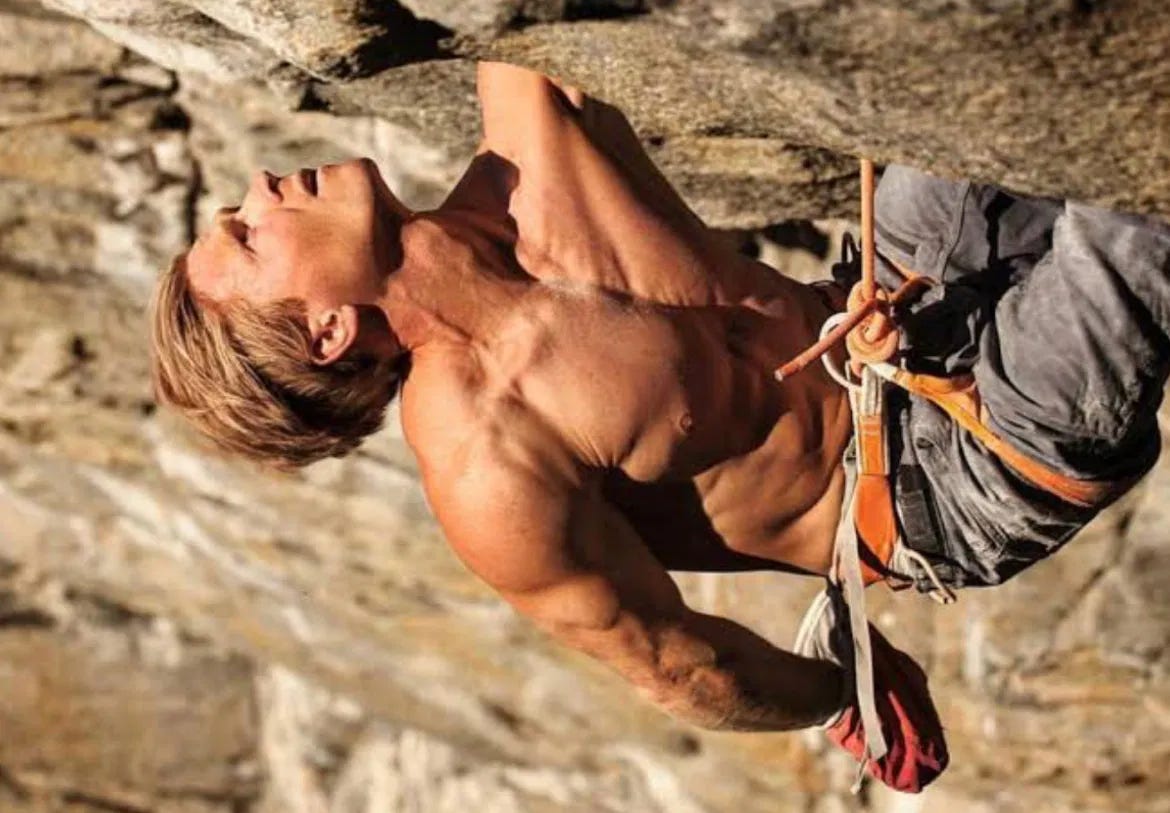

You don’t know me, but I was one of the arseholes critical of your Matterhorn solo video a few weeks back. What I said is unimportant—it was spontaneous and uninteresting—but why I felt compelled to comment is maybe more interesting and might be of use (to you, to me, to someone else).

My comment got a lot of pushback from your fans, which is funny, as I’m also a big fan, coming to the view that you’re not just a talented climber, but a unique and talented human being.

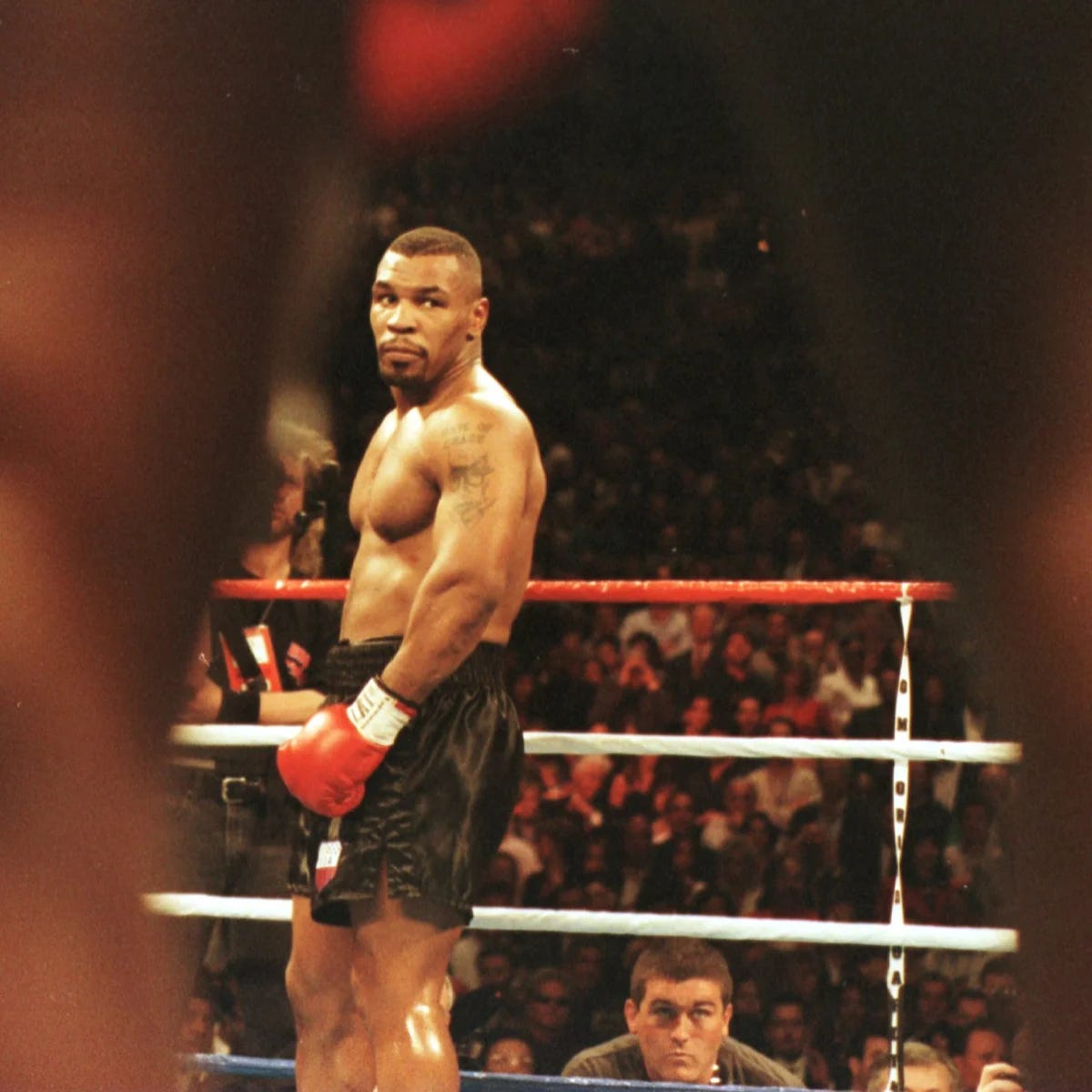

I once asked Johnny Dawes what Ben Moon’s strength was, and he replied, “His strength”. But with you, it’s more than that, and more than just skill and drive, as such things are ten-a-penny these days. You have that rare ability to masquerade as an everyman, a vulnerable mortal like the rest of us, when you’re not; you’re a demigod. Without this, you’d just be another strong climber. With it, you’re a bit of a star.

No, masquerade is the wrong word—it’s not an act, is it? It’s maybe something subconscious, deeper than an act, deeper than blood and tissue, so deep maybe you’re not even aware of what you’re doing, only understanding a few of its tiny manifestations.

But it’s this thing you do, not your strength, that makes us love you, which is why people are critical sometimes (some are just jealous and mean-spirited, or saying the things they say because they’re so dull to the world, and the pain they think they inflict makes them feel something they need to feel – human – it’s not personal, like self-harm, only it’s other-harm, butnot us—the people who really care, who were critical of your Matterhorn film. We do it out of love).

This thing you have, or maybe have (I might be wrong—you don’t know me, and you’re someone on the TV), is something most of us try to hide, as we’re all afflicted by it: something that you’ve wrapped up in bandages of strength, skill and drive, and yet it bleeds out—that inner human, not the man, but the forever child, uncertain, insecure, afraid, scared, weak. We all have it; it’s what we call ‘human’.

To point this out like a pig farmer giving a psychological profile is not a criticism; it’s just what sometimes sets the normal apart from the extraordinary, the elite from the super-elite (anyone can be elite, but only the most fucked up can become better than that).

Again, I’m not being mean; I’m trying to make sense of why I felt the way I did about your Matterhorn video, why I waited a few weeks to think about how I felt, and why I should write down my thoughts like this now they’ve settled, and send them out into the universe.

Have you ever watched the film Hamlet 2? If not, you should, as I think Norwegians have a good sense of humour (I’m not sure Alexander Megos would enjoy it, as Germans find humour no laughing matter). The film is about a struggling actor—not a good one, but one who never gives up on his dream (he writes and stars in a sequel to Hamlet, Hamlet 2, where Jesus goes back in time and saves everyone). In it, there’s a great line that a lot of people probably miss, but so cutting of why actors act:

“My father tried to stand in the way of my dreams, too. He’s dead now, but you could say, like Hamlet’s ghost, I’m still haunted by him. Because he caused me so much pain, which is why I tried to become an actor, which caused me so much pain.”

It also applies to the super elite.

Sometimes, what makes the super-elite so great is how shit they think they are, deep down—that they are shit no matter what, everything they do is shit, every success worthless, and everyone who said they were shit, or stupid, or useless, were right, no matter how hard they try (which is why they’re suckers for criticism: people who’d ignore a thousand five stars in order to focus on the single one).

The better you become, the easier hard things are to achieve, which reinforces how shit you are, as they were easy.

Why is this? Who knows—it could be one big thing early on, or a thousand small things, or coded into your DNA. Who cares. Carry the cross.

Know theyself.

Play the man you are.

I don’t think I’m saying anything insightful here, or even true; really, I’m really only writing from experience. This is what most super talent is built on. Just look at Gods and superheroes, they’re all fuckups.

But here we need to introduce a new element to this human condition: social media, primarily in this case YouTube.

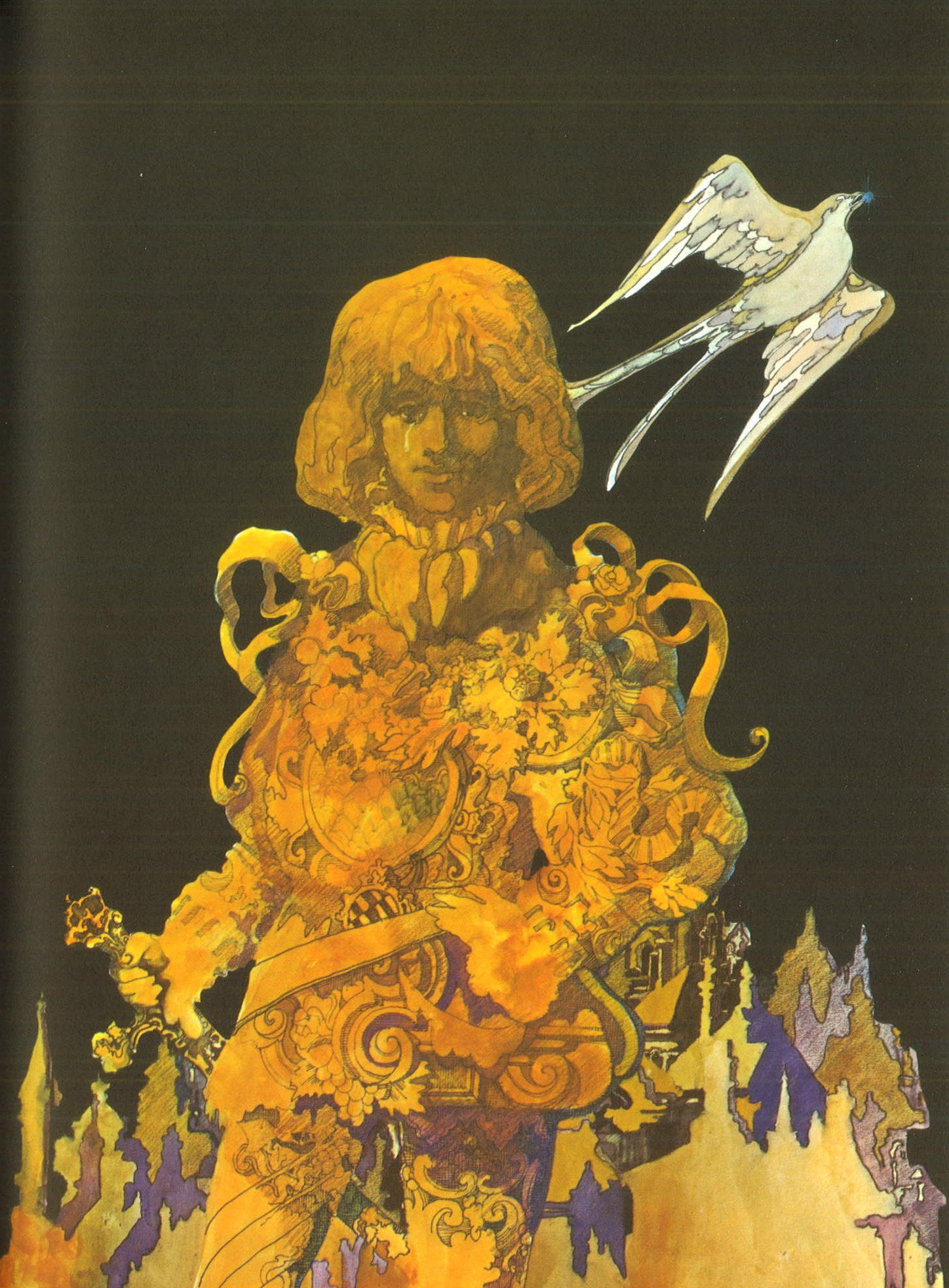

Have you ever read the story of the Happy Prince by Oscar Wilde?

As I remember it, the story begins with a city watched over by the gold and jewelled statue of the Happy Prince, set high upon a stone column. In his lifetime, the prince had only ever known luxury and opulence, but now, as a statue, he found himself staring down at a world filled with want, misery and sorrow. It broke his lead heart.

He was unable to do anything to help, until one day a swallow lands at his feet, on its way to Egypt for the winter.

The Happy Prince asked the swallow to pick out the jewel from his sword, and carry it to a starving family, which it does, but then says it must fly on. But the Happy Prince asks it to stay a little longer and carry a jewel from his crown to a begging child.

Moved by the Prince’s kindness, the swallow stays as the rest of the swallows fly south.

Each day the swallow pecks out diamonds and jewels from the Happy Prince—first from his crown and armour, and finally the jewels in his eyes—carrying them here and there, to make the world less sorrowful.

With all the jewels gone, the Prince tells the swallow to start to pick at the gold leaf that covers the statue, and carry these flakes down to the poor and needy, which it does, as the weather becomes colder and colder.

Eventually, the swallow picks at the final patch of gold leaf, flies down into the window of a starving widow, then flying back, curls at the feet of the Happy Prince, and dies.

The people look up at the statue of the Happy Prince that winter, and decide it’s so shabby that they should topple it, and melt it down to make a new one, which they do, throwing it into the furnace.

Strangely, even though the statue melts back into molten metal, there remains one part that stays the same: a broken lead heart, which is thrown into a rubbish heap, where the swallow also lies.

What kind of fucked-up mind writes a story like that for children? There is a postscript, where God sends down his angels to ‘Bring me the two most precious things in the city,’ and they return with the leaden heart and the dead bird, but most kids are too upset to hear that bit.

What’s that got to do with YouTube, or the super-elite? Well, I think the model that social media works on is a Happy Prince one—one that’s not compatible with people who need to bandage themselves up with success, fame, likes and follows, layer upon layer, but never enough to hold back the blood.

You don’t own a YouTube channel; a YouTube channel owns you. That’s not a million subscribers; that’s a million pieces of your self-esteem and meaning held hostage.

You’ve done so well. But there will never be enough. And the second you stop, you’ll begin to slip back. Then wer do you go? Onlyfans?

To me, and to many, your Matterhorn video came out of the blue; it felt desperate, something out of character, like a mental break. It wasn’t you feeding the machine, it was you—almost—being fed to the machine. Your death, your smashed body, carried down on a steel cable, giving you that final spike in the ratings: a lost life converted to content, human tragedy recycled by other people, on other channels, to their audiences.

Like I said, I think 80% of the criticism came from people who view you as more than just entertainment, content, a dancing monkey, but as a friend, or someone we’ve come to know. We love your videos, and cheer you on, like to see you do well, make money doing what you do, but that felt like someone different. You looked like a condemned man, as entertaining as watching someone fighting a lion in the coliseum (yes, entertaining for some, but no one you’d want to entertain).

If you’d take my pig-farmer advice, I’d say whatever you do, you always need to have an escape route—to game the machine, to trick the devil your soul is his, when really, you’ve got other plans. Life teaches us that reward is often no reward at all—that cheque from YouTube is worse than blood money if you become too dependent on it, what it represents. Don’t let it buy you, own you, or sell you. Periods of freedom and poverty are good for you, like leaving a field go fallow. It proves it’s you that’s in control, and cannot be bought.

Last words: someone once gave me some great but simple advice that would serve you well in this virtual world we live in, where anything you do can be made into content, which is this: “Beware of the audience.”

All the best,

Andy

If you haven’t seen it, I’d recommend watching Michi Wohlleben’s analysis of Magnus’ video. Perhaps the most down to earth and objective opinion I’ve seen so far: https://youtu.be/Y5_gAi0kLb4

Would he have done it without the camera? Was it just the content creation that motivated him. I’d say that was probably a big part of it. But I also think it could have been something he wanted to tick off personally. Could be wrong.