By a Thread: Shorts

Most of us have heard of the Antikythera mechanism, the first known analogue computer, believed to have been made during the Hellenistic period (323 BC - 31 BC) but lost to the deep for two thousand years. What its true purpose was, or method of manufacture, remain unclear, and instead, it acts as a thumb in the eye of historical certainty.

So what's the Antikythera mechanism got to do with outdoor clothing? Well, when it comes to performance and sports clothing, I often view the humble pair of shorts, long, short, short-short, sport, or leisure, is a little like the Antikythera mechanism.

No one can really identify the true origin of shorts, the point at which the plus-four or breech became a short trouser, and then the long shorts, and then shorter still. Perhaps it doesn't actually matter the why, when and how; after all, who really cares?

But as with all seemingly insignificant things, it's here, in this most insignificant item of clothing, where the meat lies, the nature of the object acting as a record of innovation, adaption, dead ends, as well as culture and utility and environment.

And so the aim of this article is to explore the short, or shorts, or to give it its full name, the short trouser, so as to understand the value of this seemingly insignificant item of clothing.

Pre-shorts

As I've said in previous articles: once upon a time, there was no gender-specific clothing; in fact, there was no clothing at all. But when scraps of animal skin were adopted, no doubt to protect migrating humans from colder nights, and then colder days, and then colder seasons, and then colder centuries, these scraps went from coverings to clothing, from animal skins wrapped around the body, too, woven fabrics, first draped and lashed, and eventually cut and sewn and fitted; you start with the skin of a rabbit and end with a spacesuit.

Both men and women wore the same clothing; it was all unisex, as, beyond childbirth, it was all hands on deck in the voyage of survival (the idea of men working and women staying at the homestead looking after the kids is really only a Western middle-class concept, and generally small children are looked after by those too decrepit to work).

This clothing evolved eventually as some variety of long tunic, made from linen in hot climates and wool in the cold, designed to differentiate one from the naked savage, as well as one's status in the group (as did adornments of no practical value), as well as protect from the elements, both hot, cold, wet, dry or windy. Capes and blankets would be used to extend the comfort range of standard clothing, as well as bolster one's protection (in the Normandy invasion, soldiers were not given waterproofs for the long and frigid ride across the channel, exposed to the elements, but three wool blankets each).

The Egyptians, then Greeks, and later, the Romans, wore what we'd now view as rough but feminine summer dresses: longer for the rich, shorter for the masses, which would leave their legs exposed for utility; no great hardship in climates that were had warm dry summers and mild, wet winters.

The utility of a short garment when working in the field, or general manual labour, be it rural or urban, is obvious (remember that almost all human populations were involved in manual labour). Having the legs free gives total mobility, allowing one to squat (vital when heavy lifting), high step (vital when climbing), and stride and run (vital when hunting). In physical combat, a naked limb is much harder to grasp or subdue, especially one that is sweaty with action, which is one reason why Judo fighters wear gis, but MMA fighters just wear short shorts. A tunic can also be made without seams or would have minimal seams, meaning it was cheap to make, easy to repair, and robust (most trousers fail at the seams, or at the knees, or crotch, which a dress does not possess).

Before the widespread use of underwear, which came about during the Roman period – which I'm guessing was not employed by working people - the short skirt would both allow full ventilation to the nether regions, as well make going to the toilet, or perhaps having sex, very easy (such things are important in a world in which survival hangs on the number of kids you can bang out).

There are also advantages of a skirt when it comes to getting wet, as the skin dries almost immediately after the rain stops, or you remove yourself from water, while trousers do not, and can stay wet for many hours (wet fabric + skin equals chafing and skin damage, and exposure to sickness and death). Elevating the fabric also reduces the risk of wetting out the garment on wet ground or when crossing rivers.

If the dress did get wet, then the fabric would dry faster than a fitted garment, or multi-piece clothing, as the skin underneath would dry rapidly due to airflow (this is one reason why people who are operating in jungles get rid of their underwear, as they just soak up water and cannot dry out).

In cold conditions, a skirt made from heavier weight fabric, like wool, can be surprisingly warm, both due to the skirt acting as a windproof layer (unlike a fitted trouser), trapping heat, which rises but also dumping moisture, as humid air falls. For cold weather, the use of socks and long knee-length garments would create some overlap, as can be seen in old school climbing breeches.

The Romans believed that to cover or bind the legs in any way was a sign of ill-health or femininity (I'm guessing the idea of femininity did not exist, and rather it was one of strength versus weakness). I suppose the ancient world did not do body positivity, and so being able to demonstrate a strong calf or thigh might well warn others to leave you alone, or else demonstrate your physical capacity to others (as we'd now look at a horse). Whatever the reason, this kind of dress, for both men and women, with long dresses saved for the elites (who did not have to work), was standard dress for thousands of years.

Enter the pant

Like most clothing, where pants came from is a little murky, but it appears that they came from China or the far Eastern equestrian societies. The reason given is that it's better to ride a horse in trousers than in a skirt. The fact that single piece woven pants have been discovered, i.e. they have no seams, perhaps points to the trouser being used to reduce friction, is vital if you plan on riding 5,000 miles from Mongolia to Poland!

Although I've never ridden a horse, I can imagine a skirt would also not be ideal in harsh weather, both wind, snow, or sun, as it would easily blow up and also leave your legs and genitals exposed if riding through bushes or woods (the Golden Horde only stopped once they found the step ended at heavily forested - horse unfriendly - land). Also, by creating heavy-duty trousers, you are creating a form of a wearable saddle that would make it easier to ride a horse bareback.

Trousers were also adopted by most Northern European people, who had failed to adopt Hellenistic dress or culture, such as the Germanic tribes and the Gauls, as well as Persians and Arabs. For the former, I suppose trousers were more fitting for living in a wooded country, while for the latter, keeping your skin covered is vital in a desert or arid environments, plus each had properly had the most interaction with the East.

And so, in the West, trousers were viewed as the dress of barbarians, the non-civilised and non-Roman. But perhaps, in ages in which the ability to survive depended on your ability to intimidate or demonstrate "innate aggressiveness", perhaps looking like a barbarian might not be so bad?

Nevertheless, just in the case of most conquests, the culture of both the victor and the defeated melded, and Gaul and Germanic dress began to be adopted by Roman soldiers (who, of course, were multi-ethnic). Putting myself in the shoes, or sandals of a Roman legionnaire posted on some winter alpine pass, or Autumnal Rhine crossing, a trouser is far more comfortable when static compared to a skirt, whose design is primarily active (one is for fighting, the other for keeping the peace), while the trouser is static. And so the soldier who was stationed far from a Mediterranean climate might go native and end up bringing this clothing back again (think of how special forces soldiers in Afghanistan grew out long beards in order to fit in culturally with Afghans, and how this was transported back to Western culture as a sign of tough masculinity).

In Rome, there was also a fetishising of barbarian ways, and what was viewed as uncivilised, no doubt a third-century version of the noble savage, or gangsta style drill music (worship of "otherness" or things that scared the status quo). For example, Roman gangs began to dress and grow their hair in barbarian styles, leading to an outright ban on trousers.

The question here is where trousers were adopted for practicality, or was it cultural, in order to differentiate between the Roman and the non-Roman? Remember that the evolution of anything does not always signify a progression towards something better. In the end, I suppose it was a mix of both, and after thousands of years of tunic, people were in need of something a bit sexier.

The short trouser

Although the Gauls had a short woollen drawstring pant, later adopted by the Romans as the Braccae, things went blank in the dark ages. Old clothing tends to either rot away or be recycled, and so our understanding of how it evolves is always, like the clothing itself, patchwork. The only thing we do know is that clothing became gendered along the way, with trousers being masculine and dresses and skirts being famine.

Nevertheless, as set out above, the trouser - a far Eastern concept - had several disadvantages for Western people.

Here we need to look at the Gaelic peoples, who we believe, adopted clothing much more practical to their environments, being wet, windy and wild (far more so than experienced by continental peoples). These people seemed to understand both the value of nakedness in combat, as well as simple wool garments, primarily blankets, shawls, and later both great kilts and kilts.

These simple items, almost monastic in style and certainly stoical, created loose clothing that retained some warmth when wet, as well as weather resistance (due to the lanolin), and could be rapidly adapted to being active or passive (the great Gaelic kilt was part clothing, part sleeping bag).

Now that "civilised" people wore trousers or at least covered their legs, it was the uncivilised, or at least the lower orders, who exposed them.

The short kilt

The short kilt, or walking kilt, appeared in the 17th century in the highlands of Scotland and was no doubt far superior for farming and fighting, important in the war against the English. This was no doubt a factor in King George the II imposing the "Dress Act" on the Scotts in 1746, outlawing both great kilts and kilts. Once this law was repealed, the short kilt became a very popular and high utility piece of clothing, perfect for a very difficult environment.

Enter the short trousers

Just as long trousers became identified as modernity and civility, the short trouser became the uniform of young boys. The practical aspect of shorts was both the reduction in cost, due to 70% less material, which is important in growing boys, as well as young knees taking the punishment of play, rather than fabric (I grew up wearing shorts and wellies for this very reason). And so, the transition from boyhood to manhood (adolescence is a post-war marketing concept) was transitioning from shorts to long trousers.

The World at War

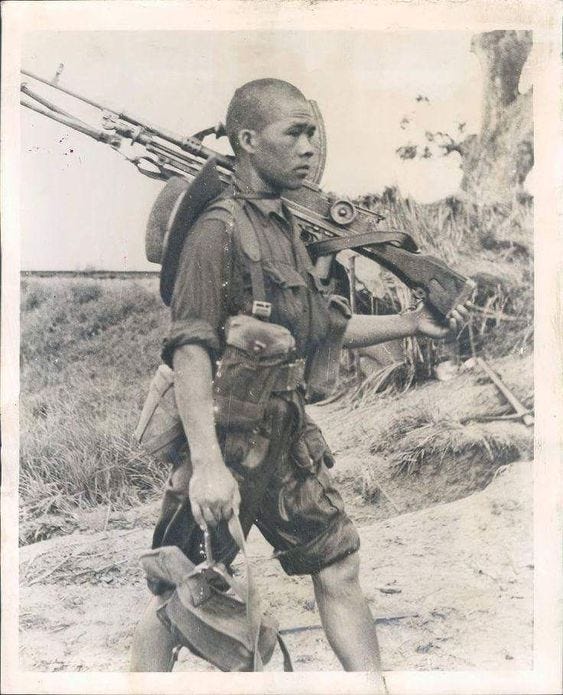

The humble adult version of the short was confined to a very small number of people who took part in sport, which was primarily for watching, not participating. But the outbreak of World War 2 changed all that, and soldiers fighting in North Africa and the Far East, finding thick wool uniforms torturous to wear, were issued instead with above the knee shorts. These shorts, made from lightweight cotton or denim, were generally cut baggy to aid movement and ventilation, and proved very popular, and very much transformed social positioning of shorts in a post-war, as it did the t-shirt.

One small detail worth covering was one issue identified with shorts was it left the legs exposed to biting and stinging insects, with malaria being one of the wars biggest hidden killers. During the invasion of Sicily, shorts were replaced with summer weight trousers as malaria was viewed as a hazard during the campaign. No doubt this issue was also one suffered by the highlanders in their short kilts. As an aside, this is why US navy SEALS adopted denim jeans worn over ladies tights in Vietnam in order to reduce the opportunity to be fed on by creepy crawlies.

Sports clothing becomes refined.

If you compare the clothing worn in the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm with that worn by Jessie Owens in 1936, you will see how sports clothing was becoming more refined, lighter, cooler, and – well – just less. Just as one of the earliest runners, the Spartan Acanthus (720BC), chose to run naked after losing his loincloth, modern clothing tried to achieve as close to nakedness as morals and social norms would allow, tunics and trousers giving way to short-sleeved shorts and short trousers, to vests and athletic shorts.

The introduction of nylon fabric in 1940, driven on by the allies insatiable need for fabrics blocked by the Japanese invasion of the Far East, was also a boon to sports clothing, with nylon replacing less robust and expensive silk and satin. These new shorts, compared to what came before, were both inexpensive, fast drying and easy to wash, and seemingly indestructible and fed into the growing movement to mass participation in sport beginning in the 1970s. Ron Hill was perhaps the Steve Jobs of sports apparel, being a major innovator in both practical design – because he was pro runner – as well as cutting edge material technology, having studied the subject at Manchester university. Just as we fail to realise the impact on the world of outdoor clothing by someone like the late Pete Hutchinson (Mountain Equipment), we also fail to grasp what an innovator and trendsetter Ron Hill was.

Although the outdoor market was slow to see the possibility of adopting sports clothing into the mountains, being traditionally attached to wool and army surplus, it was perhaps the adoption of the Ron Hill that really helped to diversify what was deemed standard outdoor kit. As for shorts, although they had long been standard kit for mountain runners, they have never really become adopted as standard kit, and in many cases, outdoor legwear has become increasingly heavyweight and industrial, matching the type of clothing worn by alpine guides (heavy-duty, patched knees etc.).

Kiwi Effect

The New Zealand landmass offers up a very environmentally diverse landscape and environment, from rain forest to grassland, barren moorland to glaciated high mountain peak, with high temperatures and low wind, storm and rain, lots and lots of rain.

Living and working (farming, logging etc.) in such an unstable environment offers up a lot of challenges, as staying dry is an impossibility. Seeing as many of the early Western settlers to the country came from Scotland, or perhaps because of that fact, they applied the dress code of the highlands, forgoing any attempt to stay dry and rather aiming to stay comfortable, a process that can be counter-intuitive.

As with the kilt, this was done by way of sheep's wool, leading to perhaps the most iconic item of Kiwi clothing, the Swanndri, a knee-length double layer wool coat, thin enough to keep your warm and the wetness away from your skin, but not so thick and bulky as to be heavy or hot to work in (Sam Neil's character in the Hunt for the Wilderpeople wears one, and early models had short sleeves).

With the top half of the body sorted, what about the legs? What do you wear in a land of rain, rivers, bogs and soaking undergrowth? The answer? Nothing, well, almost. Just like the ancient Celts, why not just run with bare legs and wear shorts? This method of dress became so widespread that shorts were even adopted as formal work dress, and internationally, you could always spot a kiwi, as they would be dressed in shorts no matter the weather.

The iconic short of the time was the Australian Stubby, which was equally the standard uniform of the Aussie man, who, like his Kiwi counterpart, saw themselves as having an adversarial relationship with nature (i.e. it was trying to kill them, only with heat, not rain).

For alpine climbing and mountaineering, shorts were ideal for approaches, especially when bashing up through the steep semi-tropical forest and through rivers and streams. When the temperature dropped to a level at which the legs became too cold, which for some was very cold indeed, a pair of polypropylene leggings would be added (Macpac or Helly). Such leggings would generally be added around the snow line, meaning rain and wetness were now less of a problem, but even here, the low density and hydrophobic properties meant it would dry rapidly as well as retain an adequate degree of wet warmth (which would speed drying by the legs). With a pair of nylon shorts (equally fast drying and windproof), worn over the top, this was a very effective system, and when matched with shell pants, I could see a Kiwi up the highest peaks. If extra warmth was required, then a more traditional fleece legging might be added, or a second base layer (lighter, less bulky, and also spare clothing for river crossings).

This Kiwi style of shorts over base layer was pretty much standard dress for many years, especially at high altitude, with the base layers very often being used more to protect the legs from sunburn.

Millennium Shorts

By the end of the 20th century, the once-obscure short, worn only by children a hundred years before, was an item of clothing everyone owned, most often having several types, including gym shorts, swimming shorts, bike shorts, cargo shorts, walking shorts, running shorts.

In the outdoor space, we now had trousers that allowed the legs to be zipped off in order to create shorts, which, although appearing to be the kind of thing only German's would wear, proved to be highly popular because they're a fantastic concept.

The lines between walking and mountaineering, mountain running and mountain marathons, rock climbing and alpine climbing, had begun to blur, especially as people had more money and time to become a multi-sport. This led to people like Ueli Steck and Kilian Jornet often dressing more like mountain runners rather than a mountaineer. The increase in speed also required clothing that could deal with a greater heat and moisture output while also being able to work for stop and go movement, bad weather etc. The trickle-down from this was mountain clothing either divided into a form of ultra traditionalism or outdoor uniform: long, green and heavy, or Sportif: lightweight, flimsy, and with a zany colour palette only an Italian could pull off. With the former, being traditional, it was ideal for traditional things, and traditional ways of doing things (walk around a lake, go to the pub), while with the latter, this required a greater level of skill and experience to work (if you were not sportif you'd freeze your ass off).

21st Century Shorts

I can't help but feel that – unless you're a Kiwi – the humble short has not really yet to find its place in the outdoors and is often overlooked when set against more traditional or more uniform outdoor legwear. This has been highlighted to me once I moved to Ireland, especially its West coast, which has Patagonia style weather. I've found I've slowly become a full-time shorts wearer, the reason being that unless I wear waterproof trousers all the time (which create their own problems), this is the best way to avoid wet trousers (I also wear Crocks for the same reason). Basically, my legs get wet, but they dry in a minute or two, wear-as, a pair of trousers might keep my legs a little warmer, but once wet, they're much less comfortable than nothing at all. I also do a lot of walking, probably around 10k a day (I do a lot of pram pushing), and I've really come to see how sweaty and inefficient trousers are. Yes, they're great if you're working in an office, but for movement, they're sub-optimal. To be frank, the ideal clothing for the West coast would be some form of a kilt, which may be constructed in the same layup as a Paramo, which seems to stand out as perhaps the most effective way to dress for bad weather. Unfortunately, I lack both the gumption to wander around in a kilt (maybe instead of trying to explain its utility, I could just say I'm transitioning?).

In terms of outdoor performance, here are a few thoughts on shorts.

Short running shorts can make ideal underwear, especially if they're made out of Pertex style fabric, as they're designed for movement, dry fast, and provide a windproof layer for your nether regions.

As all arctic explorers will tell you, the best way to stay comfortable and warm is to stay cool, and although we tend to focus on sweaty armpits, feet and hands, your groin, inner thoughts, buttocks and lower back are also high sweat areas. This issue is often compounded by the fact your waist area often features multiple layers, with top and bottom layers overlapping. I believe this is one reason why one-piece outfits tend to be much more comfortable, as it's sweat that robs you of your warmth, not the cold outside. By wearing shorts when working hard, walking uphill, for example, you're able to give maximum ventilation (best avoid double-layered shorts, as these can be far too warm).

If you can create a leg laying system that can be donned without taking your boots off, then shorts are ideal for long hard approaches, saving your insulation layers for once you arrive at your destination or when you slow. The classic system was running shorts, zipped Pertex pants, and then Buffalo salopettes, a very lightweight system that has been used from winter Scottish buttresses to Nanga Parbat. A modern approach might include zipped buff pants and a lightweight waterproof shell, although ideally, you need a thin base style layer that will transmit the moisture away from your skin, which puff style garments don't do well.

Having wet shorts can be uncomfortable if they cannot dry out, but you can buy waterproof shorts from brands like Inov8 and OMM, which can be far more comfortable than full-length trousers (or you can just cut down an old pair of waterproofs). Of course, the ideal option for wet weather would be to construct a walking kilt, or skirt, for the task, as you'd get the protection but without the sweat.

The Achilles heel of a short system is your boots, which in wet weather will probably get wet, even with gaiters. The only way to stop this would be to make yourself some boot toppers using rubber drysuit cuffs and wear this under your gaiters.

One of the biggest advantages of long trousers is the protection they give you against the sun, which is why you don’t see Arabs walking around in shorts. But when it’s hot and shady, shorts are ideal, as they allow your body to cool more effectively. And so one of the best options is to wear very light trousers that can be rolled up to make long shorts, and rolled up and down when needed. This is the ideal set up for big wall climbing.

Summery

Although no one really knows at what point the modern concept of the short appeared, what we do know is that they had served a duty and purpose for the active wearer for thousands of years, in fact, all the way back to when Adam and Eve grabbed that leaf and covered themselves up, which I suppose demonstrates just what shorts are really for, which is not the act of dress, and covering up, but as close to the opposite as possible.