Jigsaw

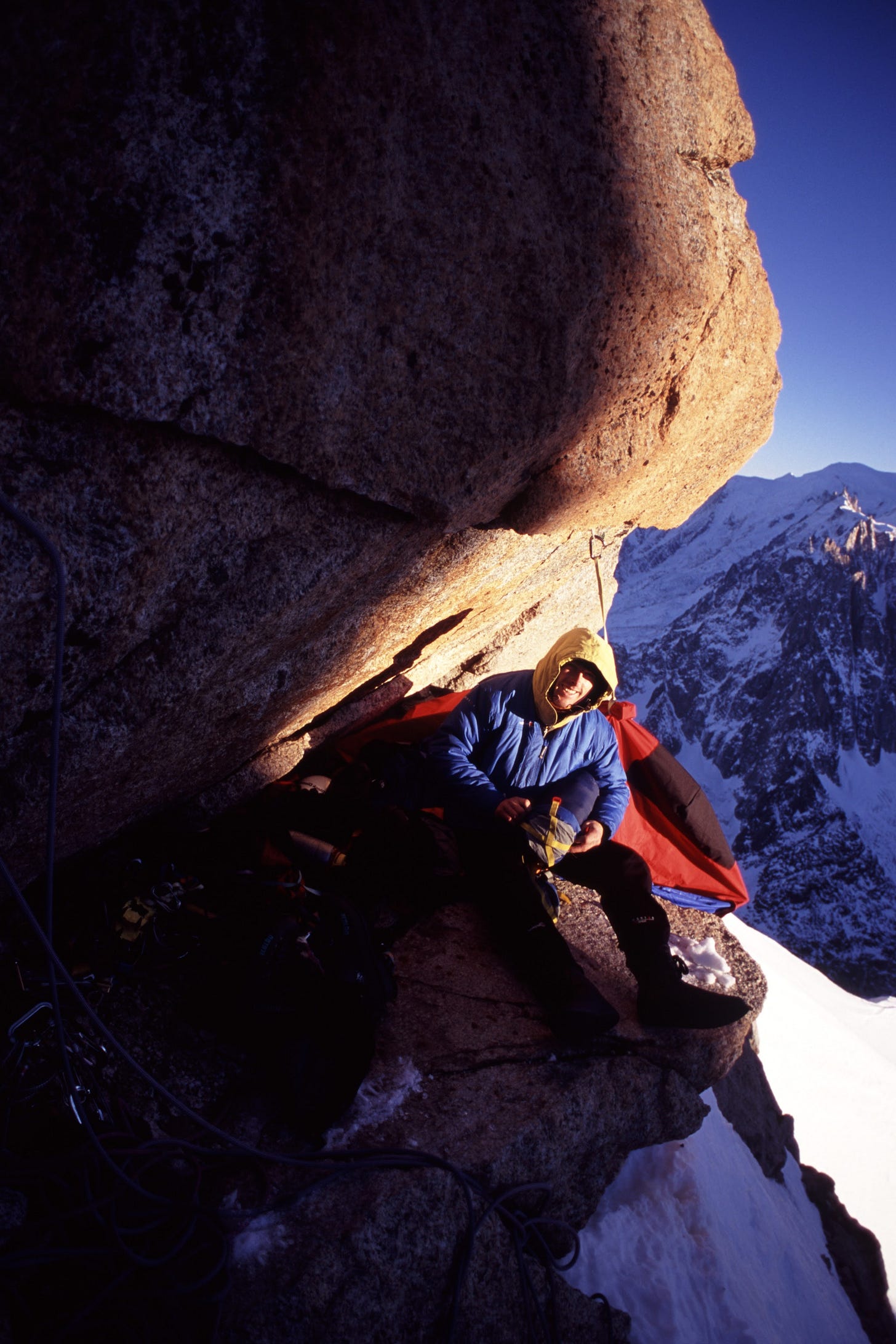

Mark Ryle / Lesueur route, Petit Dru N Face 2003

Twenty-two years ago, I made a rare (at that time) ascent of the Lesueur route (ED2) on the North Face of the Petit Dru with a complete stranger, a Scottish climber called Mark, a friend of a friend who lived in the Alps. After the climb, Mark teamed up with another friend of a friend, and got to the last pitches of Direct de l’Amitié (ED1), on the Grandes Jorasses, before getting frostbite, which ended his alpine career before it even got started (it had been a very steep learning curve). Like a lot of transient climbing partners, onto whom you entrust your life, and toil together and fight to live through some nightmare quest, I never really knew him at all, but we did share, like foxhole buddies, the bond of that climb.

Then, a few years later, Mark suffered a life-changing head injury, and as is often the case, lots of things changed in Mark’s head, me being one of them, and he took to hating me with an unhealthy passion. Maybe I deserved it, but he didn’t.

When I was writing my book Cold Wars, I wanted to include the story of our climb, as I thought it was important, but Mark didn’t want anything to do with me, so I just wrote the story, but didn’t once use his name, or say who he was. What’s sad is how amazing Mark was, a real hero, and I think my story was about that, not about me. And so, for years afterwards, people would read the book and email to ask who I was climbing with, and I’d tell them.

After Mark’s accident, he dropped off the radar, but I knew he’d moved back to Scotland, and I was always a little afraid of bumping into him when I lived in Inverness, afraid it might have ended badly (for me). Even when I left the UK, I would often think about Mark, more so than other ex-climbing partners, even though I knew him less than others.

It’s odd, it’s like when your wife catches you stalking an ex-girlfriend on Facebook or Instagram (they always catch you), and asks you why, and you don’t know. Maybe once you have a connection to another human being, that connection never really breaks, be that connection sexual, emotional, or just two 8.5 mm ropes. Is it unfinished business, guilt, regret, hope, or despair? About things you should have said or done, or things you shouldn’t? Time really does heal all wounds, unless you like to pick at them, the wound all you have left, and so I always waited for a message from Mark, some sign of forgiveness, not for me, but for him.

Then recently, I heard Mark had passed away, near Cape Wrath.

I know I write far too much about death on this Substack, and maybe I should focus more on love, or lanyards, but again and again, the thing I notice about death is not its finality, it’s the opposite, it’s leaving things unfinished. Maybe it was me who should have emailed Mark to ask how he was, even if only to find he’s just the same. Maybe not. Maybe he’d have no memory of me, or that distant climb at all.

It’s probably true about all kinds of ex-stalking, the living dead, and the dead living, people you loved, people you hated, people who meant something, people who made you feel like nothing.

The jigsaw of a life is never complete, as each of us holds onto each others missing pieces. When we go, we take those missing pieces with us, leaving the ones left behind forever incomplete. Maybe that's what a death bed is for, a place to hand over what pieces people have left to give?

I’m waffling, but, in memory of Mark, here’s the story about our climb on the Petit Dru.

I sit on a rock and cry my eyes out.

I bury my face in my knees, feeling the dirty fabric against my wet face, still gritty with rock dust and musty with days of ice melting in and drying out, the smell of a week on the wall.

I try not to cry, try to focus on the smell of the fabric, its components, part me and part mountain. It smells of action and adventure; of being alive.

It reminds me of my dad, of him teaching me to climb.

The tears come again.

The Dru stands above me.

Again.

Climbed for the third time.

It feels like the last.

On its dark side for too long now, I sit in the sun, in an alpine garden of fine grass, delicate moss and lichen and tiny flowers, the peaks and glaciers set out before me – a perfect place to be. And yet I sit crying, not quite sure why.

I rub my eyes, and try to hold the line, watching as he slowly walks away.

-

His pack looked ridiculously heavy as we dropped down from the Montenvers railway, zigzagging down to the steel ladders that led onto the glacier, the Dru standing watch over us all the while, grey in the December light.

The night before we’d argued over how much food to take, me pushing for less, him pushing for more. I’d told him Andy Parkin’s line about food: ‘why take any, you’ll only run out’, but he remained unconvinced with my lightweight philosophy.

I wanted a packet of noodles a day, some teabags and muesli bars for breakfast, whereas he wanted an alpine banquet: cake, croissant, sausage and a whole array of foodstuffs that I thought more appropriate for a hamper than a rucksack.

The reality was I didn’t feel strong enough to climb with such a load; overweight and unfit, gambling on being able to climb hard by the fact that’s what I did.

The compromise was that we would take all the food, but he would have to carry it to the route, a plan that ignored the fact that the load would still have to be shared on the climb, the leader climbing with a light sack, the second toiling up with this hamper on his back; hamper being the right word.

I’d never climbed with him before, but he had come recommended through a friend of a friend. I was told he was a guide, was ‘up for climbing’, lived near Chamonix, and with no one else to climb with, I dropped him an email, wondering if he fancied trying the Guides route on the Dru in the autumn, one of the North Face’s hardest routes and with only a few ascents. The autumn is a strange time to climb in the Alps, being neither winter nor summer, but with no one around – either climbing or skiing – it gave a remoteness to any climb. He seemed keen, and offered to pick me up at the airport, which was a good start.

Emails tell you little about a partner, and the man who met me at arrivals was a quiet Scotsman with sandy hair. He had a gentleness about him, and a melancholy, but looked strong, with a rugby player’s physique, a man who looked hard to provoke, but who’d beat you to a pulp if you did. I’m generally a bad judge of character, no doubt due to being overly positive about people, but straight off I felt he would be a good climbing partner, his easy way, good company on some gnarly epic.

In reality, I didn’t care who or what he was as long as we got up a route.

Driving back to Chamonix, I did most of the talking, and he seemed reticent about his experience, which I put down to being Scottish. The only worrying comment was that he’d only ever bivvied once on a route, which I took to mean he was very fast.

The sky was grey as we descended to the glacier, and no doubt the staff in the train station thought us foolish to be setting out on such a day, but then perhaps after a season or two you cease to care when you work in such places, and anyone who leaves the sanctuary of the gift shop or café is a fool. I joked to him that by setting out in bad weather we could guarantee good weather would arrive, rather than the reverse.

The route we hoped to climb worked its way up the North Face of the Dru, a cold hole that had a mysterious air, without the razzmatazz of the West Face, and known for being very steep and loose, with a preponderance of wide cracks, which at this time of year would be full of ice. There would be no big wall climbing like on the Lafaille, this would be down and dirty mixed climbing and alpine jiggery-pokery.

The glacier was devoid of snow, leaving only a muscled ice rink, something I’d never seen before, having only crossed it in winter before. No longer buried under snow, you could now see its surface embedded with a sharpness of stones, pieces of old rope and shards of rusted metal, giving you the impression of crossing a disused factory floor.

Careful not to trip on the detritus, man and mountain made, we crept across.

The winter snow could only be a week or so away, and I hoped it would hold off until we got down again.

The summer had been one of the hottest on record and the glacier showed signs of major change. Universities had opened up new departments in glacial archaeology as time melted away and revealed what the mountains had once swallowed. Planes had been found, some almost intact but lost for decades, as well as soldiers from the Second World War, gunned down by bullets, avalanches or crevasses.

The hard work began as we climbed off the glacier, up a hazardous mess of mud, rubble and fridge-sized blocks, blocks that had once been part of the Dru. He pointed out a spot where a young girl had been crushed, and all the while you felt as if you were in acute danger, the ground always moving, shifting and uncertain, washed by the remorseless and lugubrious glacier.

Speed was crucial, but unacclimatised – and unfit – I found my legs and lungs unable to keep up with his as he powered on, finding the way, his big rucksack obviously offering no impediment. Even at the back, his occasional halting was welcome.

I was glad I’d found such an able partner.

The glacial uplands offered an ease in angle but also a depth of snow, and again I let him plough on as the sky grew dark, night coming early. Short days would mean a lot of climbing in the dark – or if that wasn’t possible, long bivvies, and without a portaledge I had already braced myself for some bum-numbing nights sat out on the wall.

We stopped at the same boulders where me and Ian camped before climbing the Lafaille. I looked for the cave we’d spent a few days in, but found instead that it had been filled with rubble and boulders, a sign of the continued disintegration of the wall above. Looking in, and thinking of me and Ian laid there, mates and climbing partners, I felt a sudden sense of loss, and rejection; of a past life and a past self. Why wasn’t I here with him, instead of this stranger?

With nowhere else to sleep, we trampled down the snow in the lee of a leaning boulder.

I pulled out my down sleeping bag and mat and got into bed before growing too cold, taking off my inner boots and using them as a pillow, making sure everything was at hand. Winter was a calendar month away, but although the snow had yet to arrive, the cold had, and the short days only added to the sharpness.

He fiddled around, taking a long time to empty out all the food from his sack, piling it up in a neat pile beside him. I watched from the comfort of my sleeping bag, wondering when his sleeping bag might appear, or if he’d simply forgotten it, as the rucksack grew emptier and emptier. I’d seen he had a huge green down sleeping bag on his bed, but couldn’t fathom out how he’d fit it in the space he had left once he’d emptied out a shopping cart’s worth of fodder.

The answer was he hadn’t.

Instead of his big winter bag, out came a small grey tatty stuff sack from which he pulled out the kind of sleeping bag a boy scout might use for a summer camp, its faded fabric and slim synthetic lining – ironed flat by years of obvious use – showed that this was very probably the case. ‘Bloody hell, you’re going to freeze in that,’ I said, sitting up. ‘Why didn’t you bring your big down bag?’

‘It was too heavy,’ he replied – looking as if he’d also suddenly become aware of an earlier overconfidence in how warm it would be up here. I thought back to Mermoz, and my own frigid night-time terrors and shivered.

‘If you need a big thick sleeping bag in your house, didn’t you think you’d need a big thick sleeping bag up here?’ I asked. ‘…Also, where’s your sleeping mat?’ I enquired, looking around.

‘I’m just going to use this one that’s folded into the back of the rucksack,’ he said, pulling out a slim concertinaed flap of closed-cell foam, something that was nothing more than a nod in the direction of usefulness.

‘No one actually uses those things to sleep on,’ I exclaimed, ‘they’re just there to help sell a rucksack to unsuspecting punters.’

‘It’ll be OK,’ he said, as he lay down and pulled the sheet-like bag over himself, manoeuvring his body so his arse and shoulders rested on the small pad of foam.

I’d brought along a red Gore-Tex portaledge flysheet to use on the route as a tent: a kind of bag that could be hung above you to keep off the spindrift, and pulled it out and flung it over us for some extra protection; more for his benefit than mine.

We lay there in silence, waiting for sleep, feeling the cold nibbling our noses, aware of the Dru staring down at us. I knew he was in for a bad night, but he wasn’t me, so I didn’t really care, but wondered if this was why he’d bivvied so little.

The night was calm but cold, and he began moving soon after we’d lain down, seeking some warmth, a fruitless task, made even more tortuous when you know there is someone beside you who’s cosy and warm.

By three in the morning, I could hear and feel him shivering beside me, rubbing himself, in obvious bivvy hell. If we’d been friends longer, we’d have spooned together for warmth, but being Scottish, I guessed he’d have preferred death.

All I knew was there was no way we’d be climbing tomorrow. Instead of feeling frustration, all I felt was a sense of reprieve, that familiar fight or flight, doing anything to climb, only to find any excuse not to.

We woke at five a.m. and began to silently pack, no tea or breakfast, silent, accepting the way things were, that we were going down. Somehow he fitted all the food back in and snapped the lid of his rucksack shut, forcing a large triangle of dense cake in on top, then, shouldering it, began not to walk back down our tracks, but up, continuing our trail to the Dru as a purple dawn began to light.

I stood and watched him, amazed at his toughness, realising the climb was on, well at least for another day. I followed, happy for him to keep on chugging.

‘I think this is the wrong way,’ he shouted, axe scratching at a blankness that blocked his way up the intro pitches on the North Face, a steep gully blocked by overlapping slabs like an upside-down staircase.

‘No – that’s the way,’ I shouted up, ‘I’ve done it before, this is it, it shouldn’t be too hard.’

‘Are you sure?’ he said, looking down at me as if to check if it wasn’t a wind-up.

‘Honestly,’ I said, holding his ropes, wondering why he couldn’t do it, as he turned and half-heartedly gave it another go, convinced already that it was beyond him.

The minutes ticked by without any progress, until, feeling impatient, I shouted for him to come down, so I could give it a go.

Swapping rope ends, I climbed up grumpily, and without too much stress, jammed my axe into a crack, twisted it, and pulled over a small roof onto a slab, and climbed up to easier ground and made a solid belay.

‘The rope’s fixed, jug up,’ I said coldly.

Crouched there waiting as he began to climb the rope, the big rucksack pulling at his shoulders, I began second-guessing what we were doing. I thought about his sleeping bag, his skinny mat, that if he had trouble on the first easy pitch, how would he fare on the hard climbing to come? My initial acceptance of retreat had passed, and now I’d sunk my teeth in, I was in no mood to let go.

I began making some calculations.

We had very few choices: either we could push on up the Guides route and see what happened; switch to the more moderate classic North Face route, or try the legendary and mysterious Lesueur route, a climb with only a handful of ascents. If he was struggling on the first pitch, then the Guides route was out of the question, as I needed an equal partner to even consider it – the route being beyond me alone.

The North Face was a rock route, and the easiest route on the face, and so was unappealing because of that; I wanted to struggle on something really hard.

All that was left was the Lesueur, a spiral stair of vertical corners that worked its way across the North Face until it bisected with the Dru Couloir close to the summit. It would be hard, something attested to by the few people who’d climbed it; notorious also for its lack of bivvy spots, something worth considering during such short days.

‘I’m thinking maybe we should switch to the Lesueur,’ I said as he jugged up, the rucksack on his back looking painfully burdensome.

‘OK,’ he said, a positive expression hiding embarrassment at not climbing the pitch.

I thought back to climbing the North East Spur of the Droites with Rich Cross; my second alpine route, and how I’d backed off a pitch early on on the first day, unsure of myself, and how Rich had led it instead. I’d stood there and cursed myself for not being brave enough to just push on – to just go for it like he had. I promised myself then I’d never fold again and take my share, whatever that share would bring.

‘It was harder than it looked down there,’ I said – lying, ‘give me the rucksack and keep leading on – you’re fitter than me, so I might as well let you use some energy up.’

He led on up the gully, and onto the snow terrace that curved around to the North Face proper. I reckoned that being out front would exercise any negative thoughts he had, and avoid the dangerous flip into a mental position of weakness, plus with him leading, I could be carried somewhat by his strength, as we moved up past the Guides route, and on up to the Lesueur.

At first sight, the route looked forbidding: vertical corners and chimneys, stepping up over a vertical wall, traced with only a hint of ice. Once we began, there’d be no easy way off, the route traversing across the face. I could also see no obvious places to sleep.

As we stood looking up, snow began to fall, light at first, then heavier, spindrift tumbling down in showers.

‘Being so steep, we won’t have to worry about avalanches,’ I said, trying to sound positive, knowing that it was daft to carry on.

But we did.

As he moved up, a red rescue helicopter hovered out of nowhere and hung above us for a moment, the crew visible: pilot, co-pilot and winch man, all no doubt wondering what the hell we were doing out on such a day. Unsure what to do, I held up a fist to signal N for ‘no, we don’t need rescuing’, instead of two for ‘yes we do’, and, happy we were OK, and not just lost, they swooped away, home for tea.

‘Not sure seeing a rescue helicopter so early on a route is a good or bad omen,’ I said as he punched his feet on up to the first icy grooves.

‘Maybe they were just checking out potential future customers,’ he replied.

‘Eat some more donkey dick,’ I said, digging out a huge salami out of the second rucksack and jabbing it at him as snow pelted the flysheet that covered us, sitting side by side on a narrow cone of snow. ‘We’ve got to get the weight of this bloody pack down; it weighs an absolute ton,’ I said, raking around inside it, looking for the heaviest items for him to eat first.

He sat in his sleeping bag beside me, the stove purring between us: hanging by a wire from the roof of the fly, as I went on with my lucky dip, unable to eat myself, feeling sick with the altitude.

The bivvy was uncomfortable, but better for the flysheet, as snow fell outside and poured down the walls above us, its constant hiss and the roar of the stove making it hard to hear.

The minor storm had blown in during the afternoon, often obliterating all sign of him as he front-pointed upwards, showing no sign of weakness even as the weather grew grim. This time it had been my turn to struggle, jumaring with the rucksack, its shoulder straps threatening to cut off the blood supply to my arms.

I was glad I was jumaring and not climbing under such a weight.

‘Might be worth filling a water bottle with hot water and sticking it between your thighs,’ I said, imagining that this was going to be our high point after a second night for him and his featherweight bag.

He’d climbed so well, reached this tiny perch just after dark, seemingly unfazed by a night sitting on a perch no bigger than a toilet seat, just looking cheerful as we hacked away at the ice, only stopping to hide our faces in torrents of spindrift. For me, the whole thing was a reminder of what I hated about alpine climbing, the romance and machismo of it long worn thin.

‘OK, if you think it’ll help,’ he said, passing me his water bottle, his mouth full of stale croissant.

I poured in the boiling water, knowing we could use it in the morning to make tea and breakfast.

‘Don’t confuse it with your piss bottle in the night,’ I said, passing it back, a strong plastic smell filling the tent as the bottle heated off. ‘…Having to be rescued for a burnt todger would be very embarrassing.’

Dinner over, we packed everything away, switched off our torches and sat slumped, listening to the hiss, urging ourselves to sleep.

It was another very long night, and by three a.m., he was shaking beside me once more, obviously gripped by cold. Awake, there seemed nothing to say, words like ‘are you cold?’ or ‘did you sleep?’ as useless as his sleeping bag.

But again, when the alarm went off at 5 a.m., his face appeared – as our headtorches came to life – with a smile, the cold shrugged off with a few shudders as the stove warmed our little red world once more.

And so up we went, climbing, belaying, seconding with the god-awful pack, each day seemingly finishing almost as soon as it had begun; its end the start of another awful sitting bivvy.

We chose to climb two pitches each, then swap over, meaning the poor soul who’d jugged the rucksack had a rest. At one point, he almost folded again, beneath a nasty-looking crack, the face dropping away below us now, but this time I firmly pointed out it was his lead, not mine; not due to my belief in sticking to our system, but because the pitch looked desperate, and I didn’t want to lead it.

Unable to back out, he led the pitch – perfectly – and by the time he’d reached its end, he knew he’d never back off again.

As we climbed, I began to see that he was in fact the better man: stronger, faster and more positive; climbing with style and never complaining. It was just that he didn’t know it yet, but with each pitch his confidence grew. He was eating the climb up, instead of being eaten.

On the third night – another sitting affair – I complimented him on how well he was climbing.

‘It’s bloody amazing,’ he said, ‘it’s so hard and sustained. I’ve never climbed anything like this before.’

‘You must have done stuff like this when you were training to be a guide,’ I said, imagining that all guides, even fast ones like him who’d only bivvied once, must have had to tackle their fair share of hard routes.

‘What do you mean?’ he said, looking puzzled.

‘You know, you must have done some hard north faces when you’re a guide, I thought you had to do loads of grandes courses?’ I said.

There was a pause. ‘I’m not a guide.’

‘But I was told…’

‘I’m not a climbing guide … I am a walking guide,’ he said, ‘that’s why I moved to the Alps, I want to become a guide, to build up my experience, but I’ve never done anything like this … this is amazing.’

The penny dropped: the sleeping bag, backing off, the weight of food; this route was a quantum leap for him, he was a novice. On paper, he was way out of his league, on paper he was going to bloody die. In reality, he had found his mark.

We climbed on the following day, myself with a newfound respect for him as the pitches got steeper and trickier, the ropes more threadbare with heavy jumaring, the second’s rucksack never getting any lighter.

Late in the afternoon, I’d climbed up a steep crack and reached the end of my rope in a near vertical gully, the night not far off, but with nowhere to stand, let alone sleep.

‘I hope you find somewhere to bivvy at the top of your pitch,’ I shouted as he jumared up, the belay that held us both just a slung spike the size of a yoghurt pot. ‘If not, we’re screwed.’ I was glad it was his lead, and desperately hoped he’d find some glorious sanctuary just round the corner.

He took the rack and we swapped rucksacks and up he went, tapping and stabbing his way, resting his calves every couple of metres by stepping onto rock spikes that sprouted from the ice. As usual, he was steady and methodical. The night fell on us and I hung there, feeling a deeper and deeper sense of dread about what fate would bring. Standing all night would not only be hellish but also dangerous, and our only option lay above, and so I willed him on. ‘I can’t see anything,’ he shouted, his voice clear in the dark, the hiss of spindrift yet to come. ‘It’s too dark … I can’t see anywhere to bivvy … It gets steeper above me.’ ‘There must be something?’ I shouted. ‘It’s overhanging, we have to find something down there,’ he shouted back. ‘There’s nothing down here,’ I replied in bullying desperation. ‘Keep going.’ ‘I can’t… I’m coming down,’ his words almost final. ‘Don’t fucking come down here,’ I shouted back angrily, and then switched to a more desperate tone, ‘…there’s nothing here!’

‘I’m coming down.’ His words final this time.

Down he slid until we both hung from the belay, the ropes fixed out of sight above, both now desperate to find comfort. ‘Maybe we can abseil down a bit and see if we can find something,’ I suggested, trying to peer into the black below, knowing the face dropped vertically for a thousand feet at the limit of our weakening headtorch beams.

All I wanted was to stop. To just sit down and have a cup of tea. It didn’t seem too much to ask.

I slid down the rope, feeling as if I was on a fool’s errand, finding a just off-vertical vein of snow only wide enough for one and a half arses. It’s all there was. I hacked at the ice and reasoned we could cut out a slim step to sit on and so called him down to join me. He came down and we worked together, chopping at the ice with our axes, but to our dismay, we hit rock after only a few inches, our ledge no bigger than a folded newspaper. It’s all there was. Trying not to panic, we began trying to make a go of it, using our rucksacks to make a makeshift extension to the ledge, pulling the trusty flysheet over us as the spindrift began to fall again. Inside, it was a battle of slings and rucksacks and ropes, searching for a nugget of comfort, adjusting our daisy chains and knots, shifting our mats, the whole time scared that we might drop something vital; one second of inattention, and it was gone for good. We couldn’t get into our sleeping bags until we’d cooked, but just had to live with it; half standing, our crampons still on, but finally we could relax a little bit. ‘Erm, I need a crap,’ he said. ‘Now? Really?’ The main problem with the prodigious amount of food he ate was the number of times he needed to have a crap: twice a day, every day, while I had yet to go, my food intake still minimal. ‘Can’t you wait till morning?’ I said, not wanting to upset our hard-fought equilibrium between comfort and pain. ‘No,’ was the definite answer, and with that he dug out the toilet roll, climbed out from under the fly and jumared down ten feet to the edge of the ice, the blackness below. He hung there, his pants down, and went. I took a photo to remind me of this moment, then ducked back inside.

‘Finished,’ he shouted. ‘I don’t think my digestive system is taking this well.’

‘I know – I can smell it from here,’ I replied, my head buried in the fly, not wanting to impinge on his privacy; for either of our sakes.

He jumared back up, and again we shuffled around, trying to regain the near discomfort we’d had.

‘Erm… what’s that smell,’ I said, a horrible stench filling the flysheet.

‘I’ve got an upset stomach,’ he repeated.

‘No … it’s in here with us,’ I went on, trying to stay calm.

‘I don’t think it is,’ he replied, looking around.

‘Yes it is,’ I countered, the smell growing worse by the second, ‘check your boots,’ I said, pointing, only to see, to my utter horror, that my arm was smeared in shit. ‘Oh my god,’ I shouted, wanting to get as far away as possible from my arm. He looked just as shocked as me, no doubt trying to find some way to explain what we were seeing – and smelling – as having nothing to do with him. ‘Fuck, fuck, fuck,’ I shouted, totally at a loss with what to do.

Trying to find an answer, he then noticed that he’d somehow managed to crap on his boots and it was now smeared all over his crampons, and me.

A few minutes before, I’d have been hard pressed to imagine a more desperate bivvy, but now that had been trumped, and a moment later it was trumped once more, as with all my squirming around in horror, my bum ledge gave up the ghost and collapsed, leaving me hanging in my harness, my feet scrabbling, trying to hold on, while trying to avoid getting in an even worse mess.

‘I’m going,’ I said, rather illogically, as he tried to clear up the mess with a spare pair of gloves and a carrier bag.

‘I’m going,’ I repeated, flashing my torch into the night, spotting a spike of rock that looked like my only option.

‘I’m sorry, I’m going,’ and with that, I slid out from under the fly and jumared down, my sleeping bag clipped to me, and swung onto the spike, jamming myself onto it, wrapping my bag around my shoulders.

‘I’m sorry,’ came his sad voice, now hidden in the flysheet again, as I sat feeling sorry for myself, rubbing my arm on the ice, spindrift pouring down in buckets, my arse soon feeling as if I was sleeping on top of a gnome.

It’s fair to say this was the climb’s low point.

The night stretched on, snow hissing down over me, around me, into me, the only other sound the soft rattle of fabric as he shivered above.

I felt as if I’d been on this route a month.

Sleep came and went unnoticed. When I was awake, I dreamed of being asleep, and vice versa, that all too familiar bivvy limbo, but my anger passed. I wanted to shout up, give a friendly sign, a few words that showed I was over it, even if it was still all over me: ‘good here’ or some other English shorthand for sorry. I doubted I’d ever had such a strong partner, wondered if my anger was due more to my own inadequacy and frustration than anything else. Maybe it wasn’t that he was so good, but that I was so crap. But then being smeared in someone else’s shit probably does warrant an overreaction.

Instead of shouting up, I sat silently waiting for a crumb of sleep, not wanting to wake him, or break the spell of any half-sleep he might be enjoying.

Dawn unlocked us, so stiff, and I climbed back up, he apologising as we stood under our red canopy and melted some water.

‘Shit happens,’ I said.

He reclimbed up to his high point and unlocked the hardest pitches of the route, an overhanging crack, followed by a steep corner, showing persistence and stamina. The rucksack was finally beginning to feel lighter as I jugged up, glad I didn’t have to lead or second, arriving at my pitches, then climbing them slowly and with much less style.

Night came on quickly as usual as we traversed across the face on banks of big-drop snow, the steepness nearly over, the summit close. I was unsure how to finish the route, as we’d simply followed our noses so far, but now I needed a better idea. I seemed to remember something about crossing the Dru Couloir and climbing up the steep rock on the other side, but simply finishing up the couloir would be faster, getting us to the top in no time, getting this over with. The problem was we only had a single ice screw, meaning only a single runner per pitch, ignoring the fact it might be required for belays as well, of which there tend to be two.

The second problem was the state of my axes and crampons, which, being embarrassingly blunt before setting off, were now almost non-existent, my single mono-points on my crampons looking more like non-points after eight hundred metres of rock climbing.

Route-finding could wait again, as we came to the end of our traverse at the edge of the Dru Couloir and set about digging yet another pair of bivvy bucket seats.

He searched through the food bag and found mainly empty packets and wrappers, only a few scraps of food remaining. We had banked on climbing the route in four days and this was our fifth night, my appetite unfortunately now returning with a vengeance. Instead, we had to make do with some muesli bars and tea.

At least we had tea.

This night, I was determined to get some comfort, and rigged up my rucksack so I could lean against it and slept like a baby – but then babies can sleep anywhere. As I lay there, I thought about how the body adapts to such discomfort, how a sore arse and stiff limbs that cry to stretch out become commonplace, along with the cold, the climbing and the drop. Up here, once adapted, life was really so simple. Was there any wonder that people love it so much? True suffering was down there.

‘Got any brothers or sisters?’ I asked as he too shuffled around, seeking out his own piece of comfort.

‘I had a twin brother,’ he said. ‘He died.’

I left it there, and thought instead of my own brother, wondering where in the world he was right now.

As grey dawn turned to blue morning, I abseiled down from our bivvy into the chasm-like walls of the Dru Couloir, hanging from a sling while he joined me. Today we would reach the top.

As I waited, the route began to light up, my memories of easy-angled ice, ice that was sticky with axe blade and crampon spikes, fading away; instead, there was grey impenetrable ice as old as the dinosaurs. He slid down beside me and looked up, still hanging from the ropes.

He didn’t say a thing.

It was my lead first.

The dull steel of my tools made little impression on the ice, and it seemed to take several blows to get a crampon point or pick to even stick in by a few centimetres. I climbed slowly up, my arms growing weaker by the minute, my calves screaming, no doubt wondering what they had done to deserve such treatment, everything crying out for the screw to be placed. ‘Not yet,’ I told myself and inched up and up, until I couldn’t take it any longer, feeling as if I could come off at any moment, only just on.

I unclipped the screw, more careful than ever not to drop it, and tried screwing it in. It went in slowly, like a wood screw into dense timber, requiring just a little less than the force I had to give.

I clipped the rope into the screw.

I felt safe again.

The feeling was lost the minute my feet kicked past it.

I was sure I was going to fall off.

I finished long before I’d run out of rope, stuffing a cam in a crack beside the ice, telling myself I couldn’t risk climbing higher.

He jumared up and took over, leading his pitches. He seemed to be just as insecure as me, feet wobbling, axes just in, yet he climbed with far more confidence, as if he didn’t realise how he barely hung on. I couldn’t even watch, and could only anticipate the toboggan-like rush as he fell back down again.

The walls closed in on us, and the route seemed to stretch on further than I remembered, or had hoped.

Soon it was my turn again.

I looked at him, safe at the belay, and hesitated, signalling that I didn’t want to do it, that I wasn’t able.

He just sat ready under a little overhang.

I wasn’t too proud to ask. ‘My axes are too blunt, I think you should keep leading,’ I said.

‘Take mine,’ he replied, unclipping them from his harness and passing them over.

I started traversing away from the belay, heading to where the ice zoomed up around a corner, pitiless, and unrelenting. I flailed away, making movements like a man who was climbing, yet remained rooted to the spot. I had to do it, it was my turn, my lead, this was how it was, we took turns at the sharp end, it was only fair.

But I just couldn’t do it.

I knew if I did, I was going to fall.

‘I’m knackered,’ I said, stopping only a few feet away.

He said nothing.

I leaned in against the ice and rested my head against it and let out a long sigh.

I really wanted a drink.

He said nothing.

‘I can’t do it,’ I said, looking back at him.

‘I can’t do it. Please will you lead it?’

I felt the shame saying those words; pitiful, but they came easy enough. I’d have given anything not to have led that pitch.

He nodded.

I climbed back to him.

We swapped axes.

He led for the rest of the day and nothing was said about it.

The notch between the summits of the Grand and Petit Dru, where the couloir terminated, came into view just before the sun set, him boldly leading up, now the master. Out of the gathering gloom, the rescue helicopter appeared again, hovering in towards us, slipping sideways, the crew looking out to us once more.

The smell of aviation fuel filled the air, as well as the wump-wump-wump of the blades, the sound echoing back and forth across the walls, overlapping. I felt its warmth, knowing that someone cared, that someone was worried about us. We were overdue. We waved, one hand up in the air to signal ‘NO’, that we were OK, and with that they turned once more – satisfied – and swept away, dropping back to the valley, their flashing tail light fading into the night.

We scrambled up towards the summit, over rocks, speeding now, until not far below we found what we’d been dreaming of for so long: a slab of rock the size of a table, flat, somewhere we could at last lie down and sleep. We pulled the fly over us a final time and lay out, our bellies empty, but our bones grateful to lie out like the dead.

‘Well done,’ I said in the dark, the wind whipping up now.

‘Thanks, Andy,’ he said.

The descent the following day was hell. We got off route on the unfamiliar abseils, and the easy way down took all of the day, and much of the night, and it was two half-starved and very tired climbers who finally reached the Couvercle hut on the other side. All the way down, I was gripped about not making a mistake, that we had to get down safe, and it was only when we couldn’t find any anchors that we realised we’d missed the traverse halfway down the South Face, and instead had to press on to the terrifyingly jumbled Couvercle glacier below.

We made a long free-hanging abseil onto the ice at midnight, passed two fixed and frozen ropes, left by someone else who’d made the same mistake, and discovered we were in a labyrinth of tottering tower-block seracs and a maze of giant bottomless trenches waiting to swallow us, all of which we had to cross. Even waiting to be rescued in the morning was probably a death sentence.

I looked across at what we had to do, and knew I should be gripped, but instead I felt a calmness return for the first time in a long while.

‘Let’s have a brew,’ I said as I pulled down the ropes, ‘then we’ll go across.’

All I could do was let go of my fear and do my best, and cross the glacier to the other side, or not.

Our tea over, we started across, me leading, through a surreal landscape, all jumbled and out of balance, sometimes under tottering seracs the size of houses, others jumping across them, from roof to roof.

It was exhilarating.

And we made it, but even then it wasn’t over, our way down blocked by a big rock wall, the glacier sitting in a wide canyon.

Now I felt anger.

‘I’ve climbed A5,’ I shouted at the mountain’s unrelenting stubbornness and unwillingness to let us go. ‘I’ll get up this fucker.’

Then in that instant, the night took pity and a ray of moonlight shone from the cliff face, and following it, we found a tunnel, jammed with chockstones, that led us up to the hut.

The last few yards were of course through deep snow, but by now struggle was as unnoticed as breathing, as we came across the wooden hut and fell through its door.

A bird had somehow got in and the inside was full of its feathers.

We stood like Arctic explorers having found their way back to civilisation, blinking at the end, eyes only held open by the fizz of adrenaline.

The following morning, we woke when we woke – no alarms for us now – wrapped in thick woollen blankets, the sun streaming in cracked windows, feeling that familiar mountain hangover.

It felt strange to walk around without boots or crampons on, no harness or ropes; no longer tied to the Dru. Without the bulk of mountain beneath you, you can suddenly feel adrift.

We sat at the wooden table, like normal people; with grubby knives and forks and drank tea and ate from stained bowls, eating leftovers scavenged from the shelves of the hut. We hardly spoke. Not like enemies, but like friends. This was the beginning for him. For me, it felt like the end, but then it always did.

We walked down through the high alpine meadows, soon to be buried in winter snow metres deep, but so colourful now after the greyness of the Dru. I’d only been here in the winter, and had no idea it was so beautiful.

No idea.

I wondered why it had taken me so long to notice.

We stopped for a moment – because we could.

‘I wonder what my brother’s up to,’ I said out loud, hoping that he too was heading away from danger.

He remained silent.

‘How did your brother die?’ I asked, a question I knew was for him to offer.

‘He died climbing,’ he said. ‘He died climbing with me.’

He stood up and set off down.

I began to cry.

"The jigsaw of a life is never complete, as each of us holds onto each others missing pieces. When we go, we take those missing pieces with us, leaving the ones left behind forever incomplete." Fuck...

Thank you for this lovely piece of writing. Mark and his brother Gavin were my cousins and it was extremely moving and so interesting to hear about this trip in such detail. I'm sure Gavin would have loved it too.