I often come across old words in my hard drives, and I thought I’d share this one from the 90s, from my time at High Magzine.

When I was a youth, I used to scour Hull Central Library’s sport section for climbing books I hadn’t yet read. Joe Tasker had grown up in Hull, so they had a copy of Savage Arena, along with I Chose to Climb by Chris Bonington, who hadn’t grown up in Hull, so must have been very famous to have made it onto the shelf. You could tell there were other climbers in the city, as the books were well-thumbed and regularly stamped, but as far as I was concerned, there was only myself and these books—actual climbing and climbers were impossibly distant without a car, money for the train, or the bottle to hitch to the Peak or Yorkshire.

One day a new title appeared, sandwiched between a book on karate and another on golf (their sport section was never well ordered), called Al Rouse – A Mountaineers Life, a book that in retrospect was perhaps the most important book I ever read (I wasn’t a big reader, having only ever read climbing books and The Rats by James Herbert—the only book we had at home). I found it contained dozens of short stories about the late Al Rouse, who’d died on K2 several years previously, and was a sort of memorial to him by his friends. It charted Al’s life from hard rock climbs and solos in North Wales and the Peak to first ascents in Scotland, and then hard winter climbs in the Alps, followed by the dangerous game of high-altitude climbing and professional mountaineering—a combination that eventually saw him die in a small tent on K2’s Abruzzi Ridge, along with Julie Tullis (Hull libary aslo had her book), and several others.

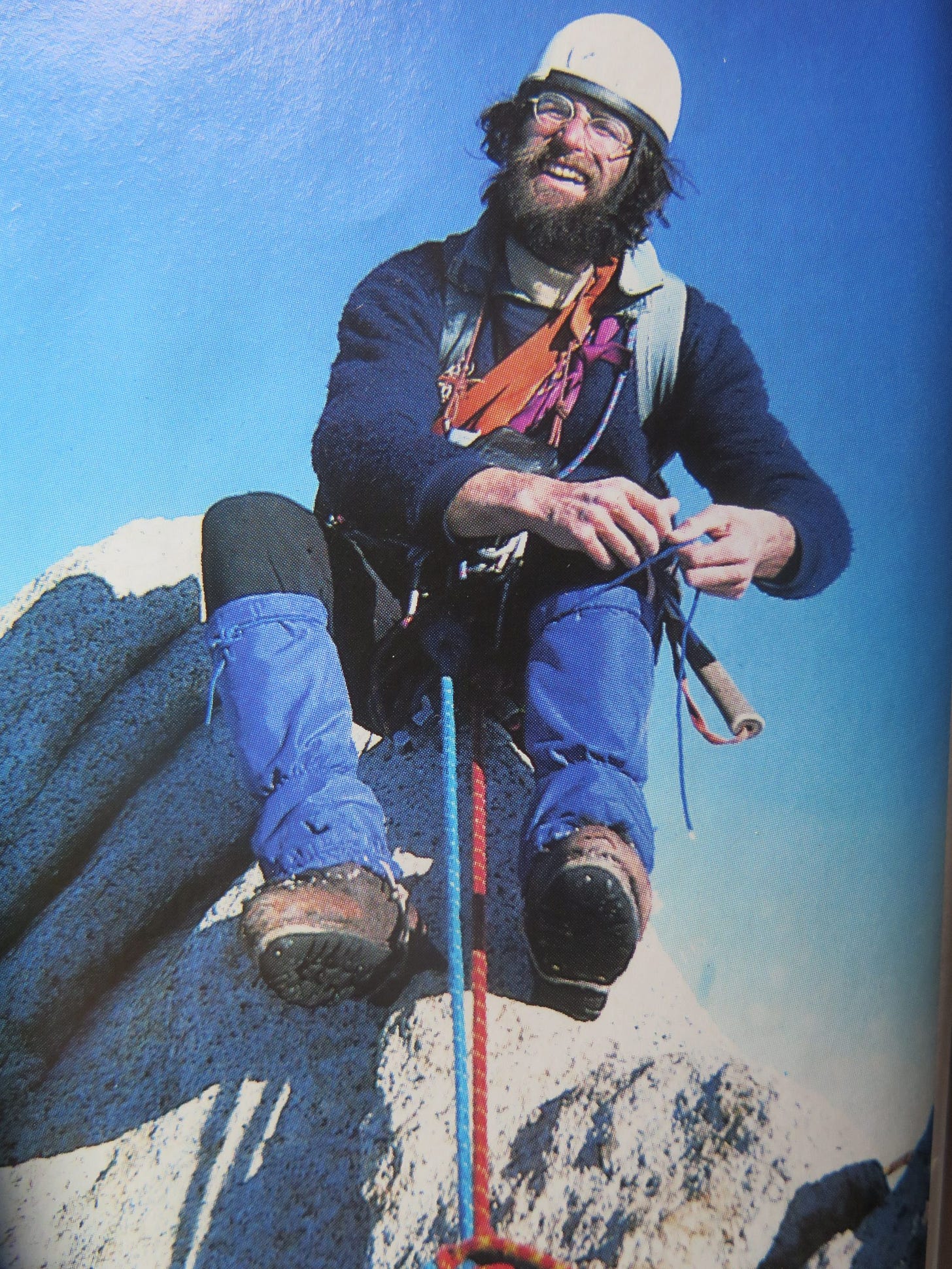

The climbing itself was impressive, but more impressive still was the colourful background to his life—the people he knew, the things they did outside of climbing, and the age they lived in. The book was full of larger-than-life characters such as the Burgess twins, Roger Baxter-Jones, Alex MacIntyre, Brian Hall, to name only a few, but one character in the book who stood out to me was Rab Carrington. Rab had been Al’s partner on many of his harder climbs, a fierce but strangely cool-looking Scotsman—a sort of Glaswegian John Lennon (he could headbutt you yet still look cool doing it).

The library also had a copy of Cold Climbs, which contained a story by Rab, with pictures of him climbing on the Ben, and although he looked like a dobber*, he seemed—even to my limited experience—to write really well. I read about Al and Rab making ascents of the North East Spur of the Droites in winter, of attempting Fitzroy, and of hard days spent in between on the grit. Most importantly, unlike many of the people in the book, as far as I could make out, Rab had survived the lot—and it seemed to me that he was the type of climber I wanted to be.

Several years later, I was working at a climbing shop in London and had the idea of organising a lecture at the Alpine Club on ‘Modern Expedition Clothing’, and persuaded the owners of Buffalo and Rab to come down to London for the evening to talk. I had no idea that Rab gear was made by the same Rab from that book until he walked through the door, and I instantly recognised him as a hero.

The first thing he asked on arriving was if I could get him a sandwich (after all, he’d just driven all the way down from Sheffield).

“Sure,” I said, “have you got any money?”

Rab’s face—well, what you could see of it behind his beard, hair, and glasses—scowled, and I think if it hadn’t been the Alpine Club, he’d have punched me for being so rude. But with nothing but a tube pass in my pocket, paying for it himself was the only way he was going to get a sandwich.

Rab put the sandwich incident to one side while he gave his slideshow, asking me if I’d give him a signal when he’d talked for 40 minutes, and then proceeded to show images of the Alps, Patagonia, and the Himalayas, and talk about how he ended up in the ‘making stuff’ business.

After talking for a long time, he suddenly stopped and shouted at me, “Do you want me to talk all night?” at which point I remembered I’d totally forgotten to keep an eye on the time. I don’t think I made a good impression.

A few years later, I moved to Sheffield, probably because that’s where Al Rouse had lived, as well as most of his partners. It did not disappoint. On my first visit to the Foundry climbing wall, the closest thing UK climbing had to Notre Dame, and the centre of that universe, I saw Rab belaying Martin Boysen, another legend (really, you couldn’t throw a chalk ball in that place without hitting a God or lesser demigod). Walking over—not sure if he’d either remember me or have forgiven me for the sandwich incident (he was a Scotsman)—I jokingly said, “Hello Rab, I didn’t know you climbed as well.”

Before I could laugh at my funny joke, Rab gave me a look as stormy as any Patagonian tempest, and I spun around and walked away.

I asked my friends if they knew what Rab did these days, as I thought he must be out doing super hard climbs still.

“No, he just rock climbs these days… he’s got kids.”

This news was pretty shocking. Rab was one of my heroes, and now it turned out he’d packed it all in. What a wimp, I thought.

With my youthful worship dashed, I got on with my own climbs, not realising that in a way I was treading through the pages of A Mountaineer’s Life, and following the same climbs as Rab (but shit). I got into the grit, then into Scottish winter climbing—doing many of the climbs Rab had done. Then, like him, I got into alpine winter climbing, doing the North East Spur of the Droites (he made the second winter ascent) as my second alpine route.

When I got back from that climb, I was full of bravado, and not long afterwards, I was working in a climbing shop when Rab came in to buy some chalk. I told him that I’d done it, thinking that he’d say “Well done there, lad,” or something, but instead he said with a dismissive shrug, “It wasn’t very hard then, so it must be really easy now.”

I told him that it had been really cold, to which he said that modern winters were warmer than when he was climbing. Then I said how our stove had broken and we’d gone two days with no water, to which he replied, “Aye, so did ours.” I just gave up and felt deflated as I took his £1 for a block of chalk.

I would see Rab from time to time, each time telling him what I’d been up to, hoping that his face would crack a smile and he would say, “Well done.” But whether it was climbing Scottish VIII, soloing El Cap, or failing like him on Fitzroy, it made no impression. In the end, I think he just thought I was this annoying bloke who would constantly be pestering him and showing off, a big mouth. I guess I was on the outside, strangely full of myself, but all such people tend to hang all they have on the outside, for show, leaving nothing within.

I think things came to a head at a party one night we both ended up at. We were both pretty drunk—I had never been, or will ever be, as drunk—and I think maybe Rab was the same. He was talking to a bunch of people about hitchhiking, and I made the mistake of butting in and saying, “Never hitch in groups of 10.”

The next thing I remember was that everyone was walking away, leaving only me and Rab, and he was poking me in the chest, saying, “Why don’t you shut up—no one wants to hear what you’ve got to say.”

I then remember walking away, but it turned out that I’d started poking Rab in the chest, saying, “What’s the matter—scared of a little competition!”

As I walked away, Rab started after me, but luckily for me, he fell over some chairs and I made my stumbling, unaware, escape (It wasn’t long after that incident that I read a profile of Rab, which began with a description of him entering a chip shop one Saturday night and everyone cowering, afraid of what he might do to them if he was in a bad mood. Oh, and Rab was thrown out of both the Alpine Club and the SMC, by the way.

The next evening, I was at Burbage with some friends and we bumped into Rab.

“Have a good time at the party, Rab?” one of them asked.

“Aye,” he said, “had a bit too much to drink though… but not as much as some people.”

After that, I only saw Rab from time to time—but gave up talking to him, no doubt much to his relief. I guess, in the end, I grew out of that hero worship part of my life.

The last time I saw him was at a party at my editor’s house, Geoff Birtles’, and maybe it was because we were both sober, or because both our wives were standing next to us, but we had a civilised conversation.

We didn’t talk about climbing, but about kids, and about Rab’s daughter moving to Hull to go to university. Rab was really animated and talked with the same enthusiasm that pervaded his writing.

“It’s got a great library”, was all I had to add.

He talked about running a company, how one day you’re sewing up sleeping bags in one end of a shipping container, with thoughts of how to escape, to the next, you have countless employees and their families to worry about; how even when you own the business, really, the business owns you.

After we’d finished talking, my wife said,

“What a nice man Rab is—you make him out to be some kind of monster.”

It’s nearly 35 years since I read A Mountaineer’s Life, squatting on the dusty floor of Hull’s Central Library. It was one of the early books in my life that somehow inspired me to imagine that this life could be an adventurous one, as lived by its cast of characters. In another aisle, in another bookcase, perhaps another book might have been calling, another life, but it was this book, and that life I opened.

Life...is like a box of chocolates. :)

Interesting story. Scott Stewart and I met Rab, Al Rouse and two other UK climbers at the Gunks in October 1973, if I remember correctly. I think we all climbed at Skytop one day but I was certainly on easier routes. Later we all spent too many hours drinking too many pitchers of beer but I found Rab and his buddies to be fun and interesting.