The Kill Pause

Before I start this piece of writing, I need to give some background, as this hasn’t been easy to write, but I felt compelled to write it.

Yesterday, someone sent me a video showing the death of the 23-year-old climber Balin Miller, killed while rappelling the last pitch of the El Cap route The Sea of Dreams to unstick a haul bag, after his solo ascent. They suggested that I may be uniquely qualified to turn this tragedy into a lesson that might save a life—a teaching moment to avoid another easily avoided climbing death. My qualifications to comment like this being that I’m not only one of the few people who have soloed the Sea (I think it’s had less than 10 solo ascents in nearly 50 years), I’d also soloed El Cap several times, and had written a book on the subject of how not to die rappelling. I’ve also used my nine lives nine times over. Some might think I’m writing this to sell more books, or insert myself into someone else’s tragedy. I’m not; I’d rather not have to write this at all, as all I seem to write about is climbers dying of late.

I clicked on the video and started to watch—Balin’s last moments captured by someone with a telephoto lens down in the meadow—then I clicked stop when I realised the film was actually going to capture him falling. I’ve spent my life avoiding such snuff content; it’s sick. It lives in your head forever like a wound. Then I scrolled through the comments below, and the sickness was plain to see: fellow humans, only numb, cruel, desensitised, detached, thinking themselves moderns, when really, they’re just a scabby mob—the types to cheer as someone is burnt at the stake, or hanged, drawn and quartered. These people have so much cognitive scar tissue, digitally brutalised, that they can’t feel anything any more. This film, these people, this world we live in—the virtual one—cheapens death, the loss of this young, amazing life recycled into nothing more than content, something to pass a few seconds before swiping onto something else in an otherwise spiritually empty day.

And so, in spite of the content and the comments, I clicked play and watched it to the end, saw the tragedy unfold, as I’d already guessed it probably had, having been there, and nearly done that very thing more than once. It wasn’t a rookie error, it was the opposite, a masters error.

If he was going to die, let it be for something more than cheap entertainment for people like this.

If you think I’m being insensitive, then don’t read on, but I think I’m just hard-hearted these days, sick to death of climbing deaths like this—not only robbing someone of a son, brother, friend, partner, perhaps the love of their life, but also what he could have become, what that person could have been. Dying like this is quick and easy, fourteen seconds and you’re out, and although such a common tragedy leads to much eulogising, Hallmark card tributes in comments and on forums, trite cut-and-pasted one-liners and poems about lions and sheep, within a few days it fades to just yesterday’s news, yesterday’s man, just another lost talented climber.

Apart from all who loved and miss him.

If the dead could speak, if Balin could speak, the first thing he’d say would be sorry, and the next, to explain how it happened, so others wouldn’t go that way like him. By writing now, maybe one life—spent—has enough power to save others.

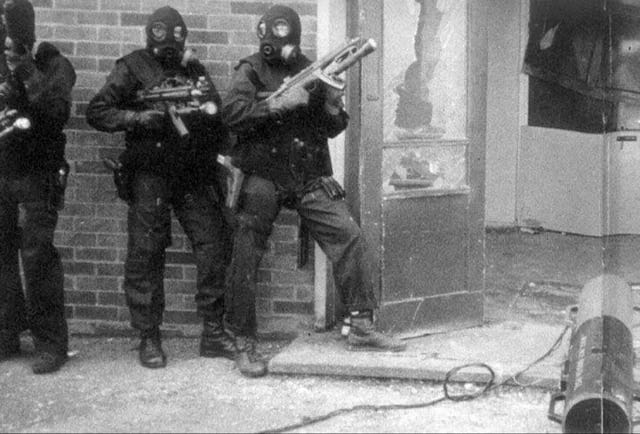

I once had breakfast with a bald-headed killer, a member of the British SAS, a real tier-one individual, a John Wick type who could take out the whole table with just an egg cup and spoon. He was currently on a six-month counter-terrorism role, CQB (Close Quarters Battle), cycle after cycle of room clearing, storming buses, trains and aircraft, firing off thousands upon thousands of rounds of live ammo. This kind of training he was doing was the definition of Mark Twain’s “Continuous improvement is better than delayed perfection,” every six-month cycle a refinement of the last, these cycles having begun in 1972, following the Munich Olympics massacre.

It’s not often you get to meet a well-trained killer and trigger man like this, and so I asked him lots of questions as we ate breakfast. Two things stood out.

The first: he told the story about how he’d recently been practising CQB in the “Killing House”, as he did most days, every action and reaction rehearsed again and again until it became instinctual and unthinking. In one room assault, they had all lined up in position, ready to blow a door and storm inside after throwing in stun grenades, when, unexpectedly, a blast of wind rushed up the corridor, and the door swung open by itself.

Never, in all their training—perhaps never in fifty-three years and a hundred and six cycles—had this happened before. There was no standard operating procedure or pre-installed action to take. For a second, no one moved; no one knew what to do. And then they did, and they all reverted to the default: attack.

I don’t know why, but this story—of the blown-open, not blowing-open door—had a big effect on me. It seemed to mean something important and needed remembering. It stuck.

The other thing that stuck was when I asked him how long it took to decide who to kill and who not to kill—no easy thing in darkness, fire, smoke, screaming, gunfire, air dense with panic and fear, knowing all the while that someone in the room you’re entering might have a gun, and would die happy if they took you with them. He explained that you were trained to pause for a fraction of a second before pulling the trigger, a span of time that few would even perceive, the shots appearing to be instantaneous to you or me, far quicker than any terrorist could respond to and shoot first, yet paused just a moment. That split-second helped to settle the aim, to reduce the target-missing finger-jerk, make the shot a conscious and controlled one, overriding that well-trained unthinking instinct to kill. That pause—the kill pause—as brief as a flash of lightning, would allow you to identify who you should kill, and could well define the rest of your life, and someone else’s.

How did Balin Miller die?

My hypothesis goes like this:

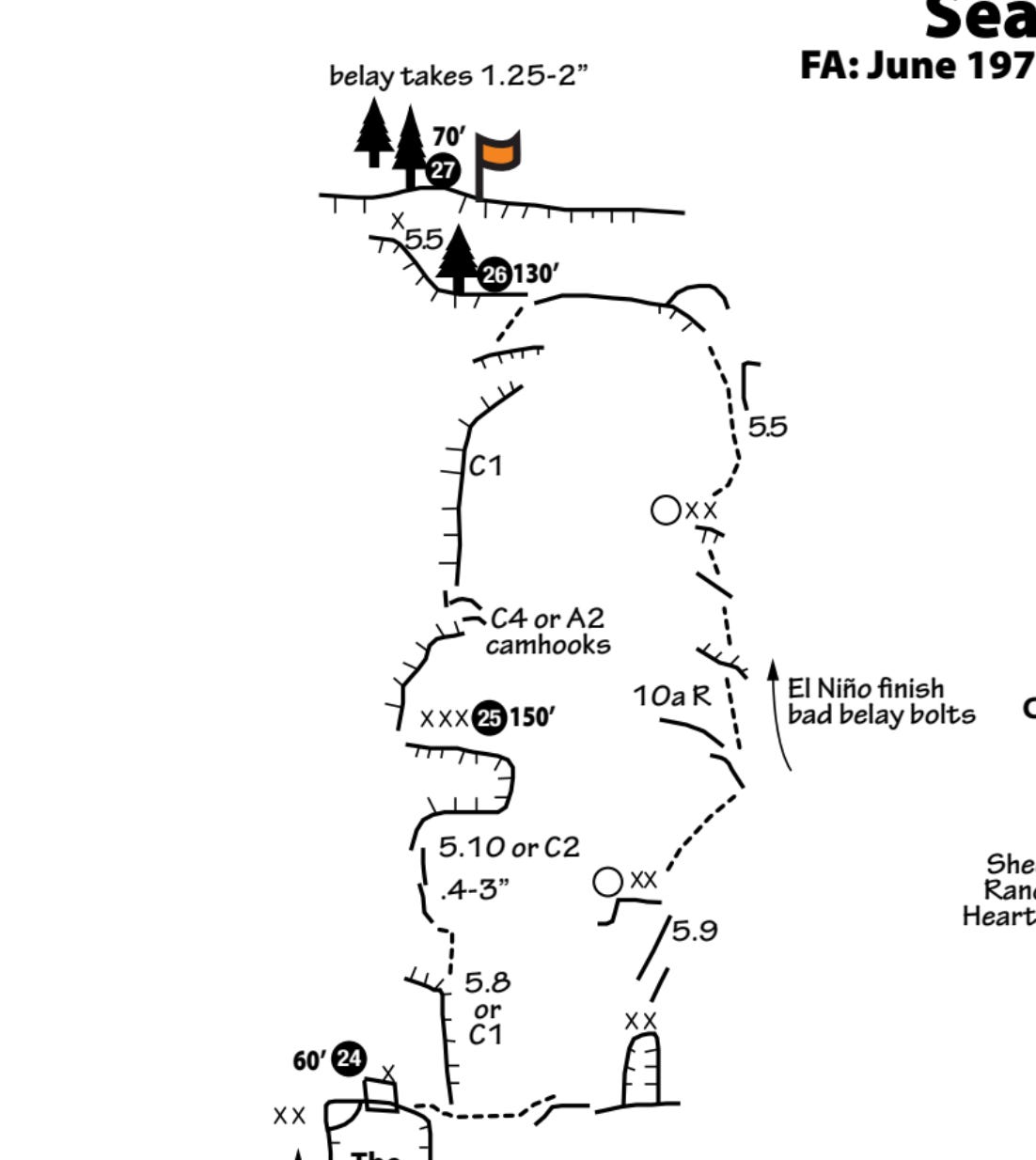

I would say that he climbed the last pitch of Sea of Dreams, which is 130 feet long (40 metres), then after making a belay and attaching the haul line to his hauler, he rapped his static haul line—which was probably 70+ metres long—back down to the lower belay.

Once back at the lower belay, he saw he had a lot of spare haul line left (30 metres?), and needing to lower out his haul bags, he tied them in short and lowered them out using the end of the static, leaving a very long “dead” tail of static line and shortening the amount of active rope between the bags and the hauler.

He cleaned the pitch by jumaring the lead line, and having regained the top anchor, began to haul the bags, the bags hidden from sight by an overhang.

While hauling, the bags hung up, as they often do when soloing, while still some distance from the anchor and would not budge.

The only option was to rappel down to the bags to unstick them. He could have rapped on the lead line, but by rapping on the haul line, he could carry out a counterbalanced haul, assisting the bags as he re-climbed the static line.

I’m sure this was the last thing he wanted to be doing so close to the top (there is a short scramble left), and all he wanted was to get down, eat pizza, have a shower, shoot the shit. He was probably also buzzing with excitement, and some relief, as soloing the Sea of Dreams is not without risk. I also expect he was yet again feeling the relief of having come through another gnarly climb.

He didn’t want to go down, but he had to, so he decisively got onto the haul line—as he had all the way up the wall—believing there would be more than enough rope to reach the bags at this point.

What he probably forgot was that he’d shortened the haul line by many metres by using the end as a lower-out line. And so, as he rushed down the rope—the bags and rope end hidden below a roof, as he had done for days—before he even knew it, the end of the rope—the bitter end—had passed through his GriGri, and that was it.

If anyone knows Balin, and can’t imagine what went through his mind in his final seconds, fully aware he was about to die, all I can say is that I’ve had a few moments like this, not when I thought I might die, but when I knew I was about to die (but didn’t), and all I can say is it’s not how you think it would be. There is no fear, or anger, or bitterness, not even terror. There’s only acceptance. There’s no fight. There’s only peace. Maybe it’s the chemicals in your head that make you feel this way, but I hope it’s more than that.

Was Balin’s death avoidable? Yes, but so are most climbing deaths, and death in general. It wasn’t a single failure, like he just “rapped off the end of his rope” or failed to tie a knot in the end. He died like most climbers die: he’d grown too comfortable with what he was doing and where he was, and he rushed when he should have taken his time. He thought it was over. He let his guard down. It wasn’t.

And so it goes.

I’m no paragon of safety; I’m not passing judgement, but I do mourn and I take it personally. I don’t know why.

You can draw your own lessons from this sad story, but I think it’s worth remembering this idea of the kill pause. Whenever you’re doing something high risk, especially high risk and rushed, before you commit, before you unclip, or go, or begin, take a fraction of a second to double check you’re in control, fully aware of your environment, and yourself, and everything that keeps you tied to the living — the kill pause, only a moment, less even than that, but something could well define the rest of your life.

Thank you, my friend, for putting the human back into a story that had been dehumanized by the modern equivalent to the peanut gallery. They took a thirstily-lived life they could not understand and turned it into the only thing they had the capacity to understand, "content, something to pass a few seconds before swiping onto something else in an otherwise spiritually empty day." And our community is spiritually poorer for the passing of a talented, competent and inspiring young man.

Andy, you’re an incredible writer.