The problem with skinny singles

The issues arising from the widespread use of the thinnest single ropes.

INTRODUCTION

If I was to be asked to name one aspect of modern climbing technique that I feel uncomfortable about, it would probably be this: how non-elite climbers – which is pretty much all of us – have begun to adopt the ultra-skinny single rope as the standard, meaning we’re increasingly moving away from double rope techniques. I think for the majority of climbers, new, old, and yet to be born, this is a mistake.

This change, which came about due to a number of influences, including sport climbing, gyms, and the Americanisation of international climbing, and has now spread to all styles of climbing, including high-risk terrain where terminal rope damage can occur.

This is not to disparage a single rope technique, but only to consider that like any tool, its function and its limitations need to be understood. A sledgehammer and a toffee hammer are both hammers, and although both do the same job, it’s best to know the difference between each.

The following is not meant to chide anyone, especially not novice climbers or rope manufacturers, but more about stepping back and asking some questions, as well as a chance to reconsider the utility and safety of double ropes.

What is an elite or non-elite climber?

First some clarification. An elite climber is any climber who has developed the highest degree of competency through practice/experience and is in the top tier of the sport, i.e. they get their ropes for free, as well as everything else. This means they are very capable of judging what gear is appropriate to a climb or project and will tailor it to fit, what they deem appropriate often departing from agreed-upon safety norms and margins, aka, “don’t try this at home”. Many elite climbers use gear in ways that would void the warranty.

An elite climber is also likely to use this knowledge to make calculations about safety while maintaining an acceptable safety margin, the aim always to find that point between failure and recklessness. Note that in the high-risk game of elite climbing, such as alpinism, speed climbing, soloing, failure and reckless abandon can both result in death, the big full stop.

Success, if judged by your peers as suicidal, maybe applauded in the short term, but tends to be born out as such in the long term.

What elite climbers views as acceptable would generally be viewed as unacceptable in a court of law. For example, the late Ueli Steck may have been able to rappel down a 3000-metre face using 5 mm ropes, but your average climber following his example, and rappelling down a sea cliff, would be judged as foolish and dangerous. It’s all about ‘the line’, and elite climbers tend to believe they know where that line is, even if it proves to be ego generated self-delusion (but it serves the purpose).

It would be a mistake to view elite climbers as masters of risk, as “they do it, it must be safe”, as this is not born out by when you look at their high fatality rate. This sad fact is both a reflection of the amount of time they are exposed to risk, compared to a non-elite climber, as well as intentionally ignoring what’s considered safe, because safety comes at a cost. Cut out that cost, cut the corners, can help you achieve elite status, death, or both.

What I’m trying to say is that when we see X superhuman climber on the North Face of the Chosswand, climbing on a single strand of 8.5 mm rope, we need to separate out that from what is applicable to us mortals in the real world.

Going Skinny

Single ropes had long been the novice’s choice; chunky 11 mm ropes that could tow a cruise liner. But real men had two ropes; alpine climbers, climbers who went to the greater ranges, climbers who had gained some mastery of the sport.

But as sport climbing grew in popularity, the strongest climbers began to only need one rope, and what was once ‘climbing’, was demoted in some way to being ‘trad climbing’, their double ropes becoming a bit fuddy-duddy. The real masters had only use for a single rope, and soon so did most climbers.

At the same time, there was a sudden shift in focus from European climbing, which until the rise of sport, would have been led by alpine guides, towards American climbing, and how they did things. People began to see American climbers pushing the limits, as well as magazines and videos (pre-internet), with most climbers using only single ropes. It all seemed much more modern.

I remember a friend climbing with the late Alex Lowe - a five-star legend - in Bristol, telling me how they’d just climbed on a single rope, and how radical and simple it was. I also remember looking at pictures of Mark Twight climbing alpine routes with only a 10 mm rope and it just looked so hardcore, and bold, and so I did the same. This seemed a great idea at first, apart from if you had to carry the bloody rope, but less so when we had to bail off 500 metres up our first route (I didn’t know Mark had another rope in his bag).

An early classic sport rope was the 10 mm Mammut Galaxy, which in the 90s seemed radically skinny (Ben Moon did use a Mammut Genesis 8.5 mm rope when he climbed Hubble). But slowly the rope diameters crept down bit by bit, until it hit the magical 9 mm, and then went even further.

Now we have the Beal Opera 8.5 mm rope as the thinnest single rope of the market, which is funny, as I’m old enough to remember when 8.5 mm was viewed as thin for a double rope!

The thinner single ropes were also being produced to fulfil the demands of mountain guides, who even when climbing with two clients, had to employ full strength ropes for each, so had to use two single ropes.

I suppose there might also be a commercial element in these new super-thin ropes, in that there’s a ropes arms race, in which the big brands fight it out to be the thinnest and the lightest, basically, what’s the least you can get for your money.

A thinner rope will also be viewed as more technical, but can also cheaper - even a premium rope - than some old school 10.5 mm workhorse rope simply because there’s less rope in your rope.

Imagine you’re new to climbing and go down to Decathlon to buy a rope for the climbing gym. You see a 10.5 mm and 9 mm single rope, one heavy and expensive, the other lightweight and cheaper. The shop assistant tells you to buy the cheaper one because it’s a nicer colour (you don’t know it, but his area is actually football boots), and you do.

What was not really thought about, was these super-thin ropes are like Formula One racing cars, not London taxis. They are highly specialised, designed for cutting edge climbers on cutting edge routes, and in some way they were disposable, or so it seemed.

That person with the new red 9 mm does have one of the lightest ropes in the gym, but also probably one of the least practical, least robust, and in some ways, the most dangerous when learning to belay. A solid 10.5 mm gym rope, will probably last for several years, while a 9 mm one might only last a few months of heavy use. This is why you’ll tend to find experienced gym climbers climbing on tug boat ropes, often cut down from full-length ropes, while the novice is on something as thin - and long-lasting - as dental floss.

Rope progression

When selling ropes to new climbers you’d always talk them up to a 10.5 mm first, and then later into double 8.5 mm ropes. The reason for this is really all climbers need three ropes, using the system that’s most appropriate. Starting out climbing it’s best to use a single, as this keeps it simple, cheap and helps develop good skills in minimising rope drag. A single rope is also ideal for top and bottom roping, another crucial part of learning. A single rope is also necessary for gym and sport climbing.

Once you’ve mastered the single rope, you move up to two ropes (you can double up a single on short crags to learn), as you’ll now be climbing harder to protect single pitch routes as well as multi-pitch climbs.

I think this progression changed with the Beal Joker, which being a good price and having the right weight and size, seemed to become the new novice rope of choice, and opened the flood gates for skinny ropes, some climbers even using them as double ropes. It was also the first rope that passed as a single, half and twin rope, which sounds impressive, but really it’s only the first that was ground-breaking.

At the same time, there was an explosion in hard mixed climbing and you’d see people doing hard and bold routes with a single rope, having just translated sport ropework and fitness into winter.

This led to mountaineering objectives, long the home of the double rope, now being climbed with a very thing single rope, the idea to simplify the system, to be fast and light.

This obsession with speed also played a part, as short fixing and belayed moving together (using micro ascenders), as well as fast coiling and short roping, only really worked on a single rope. Very soon you’d see people climbing the big North faces on what looked like a single strand of dental floss, as well as big walls going down by climbers dressed only in shorts and using the skinniest of ropes.

Gym Gestation

An alternative view on double ropes is that many climbers began to see them as a ‘pro’ technique, especially climbers who came out of gyms (which is most climbers). Many has been the time when someone has said, “wow, you’ve got two ropes, cool”.

I’ve also climbed in lots of places where people seem to view themselves as sport climbing, but on trad gear, and so make their climbs unnecessarily difficult and dangerous by treating them as sport routes.

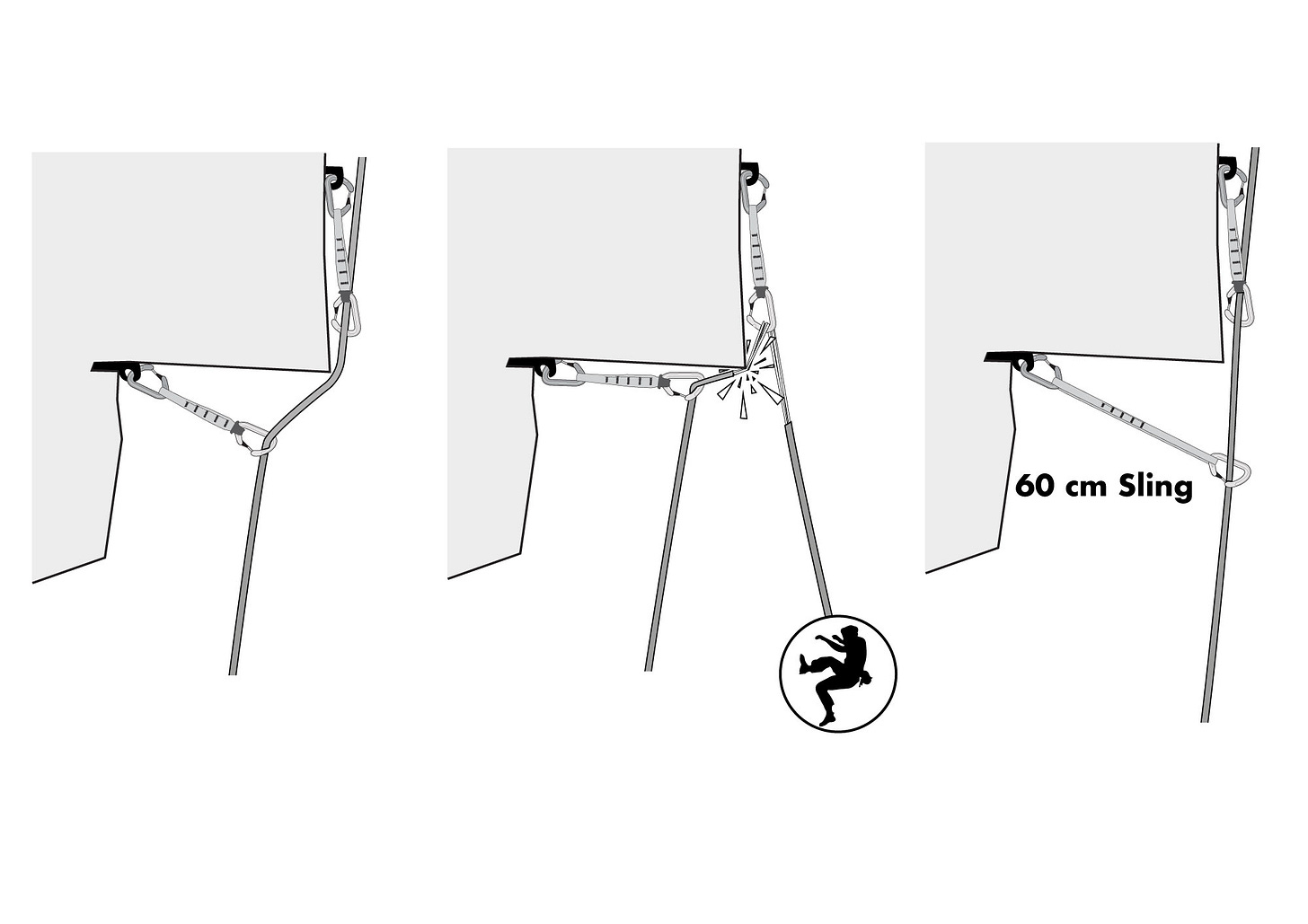

This was best demonstrated by seeing someone climbing a moderate route in Arapiles, a route that zig-zagged a little, who used 120 cm slings to extend all his gear in order to reduce rope drag (some of his low gear, due to traversing, had the rope almost trailing along the ground).

They see double ropes as trad ropes, but they’re not trad climbers when really the safety aspect is just part of a two rope system.

Single Rope Negatives

Of course, not everything is rosy in terms of single ropes, so here’s a list of problems.

On Rappel

In the modern context, unless you’re climbing on some fully bolted ‘plaisir’ style multi-pitch crag, designed for easy descent, one that has rap anchors set at 30-metre intervals, you’re going to need two ropes to get down.

In the US and US-centric climbing nations (like Canada and Australia), this generally means you either carry – or trail – a second rope, your rappel rope (also known as a zip line, haul line, trail line). Such a rope can be something lightweight and high tech, such as the 6 mm Petzl, Beal or Edelrid rap ropes, but on observation, it tends to be low tech, just dragging up another full-size single rope.

Climbing a route with a high tech single rope, such a 9.5 mm, while trailing a second single rope, like your old 10 mm rope (the one that’s been replaced by your fancy 9.5 mm), never seems logical to me, especially as the second rope is never used as a lead rope, but just dead weight until you get to the rappels. The use of the two single ropes for rappel is also problematic, as they’re much heavier to pull and are more affected by friction.

A second issue with this trailing system is it often gets jammed, especially when the leader leaves it up to the second to trail rather than clip it to their harness, the rope often hanging up as it tries to uncoil itself on the ground or at the belay. This leads to all sorts of time-wasting and hang-on-a-minute-isms.

In windy weather, the trail rope can also be blown around and hang up, as it’s not clipped into any gear, but is just hanging.

And of course, you are also carrying in two single ropes, which is not ideal on a long approach.

In Europe, climbers don’t tend to use this system, and either carry a thin rap rope (6mm), or double the single rope with a half or twin one, and will switch between just clipping the single, or mixing it with double rope technique, or even twin (clipping both ropes into a quickdraw). Again this system, although feeling kind of modern and hardcore, is not ideal, as it’s just a heavyweight double rope system.

A more advanced single rope descent system would be to use a lightweight pull line, such as 60 metres of 3 mm Dyneema, and use blocking techniques, or a Fiddlestick, or a tool like the Beal Escaper (although at 100 grams, it’s adding weight to your ‘lightweight’ system).

The bottom line for me is that if you’re climbing multi-pitch routes you want to be able to do full-length rappels, and so a dedicated double rope system is the way to go.

Chop, cut, snap!

For me, the biggest safety issue with a single rope is that it’s a single rope; if it breaks, so do you.

But do ropes break? Well let’s start with a story I once heard in Yosemite valley which may be true, or maybe apocryphal, but’s worth sharing either way.

The story goes that a climber was leading a pitch on the Nose, one that climbed around and around a corner and out of sight of his belayer. Perhaps it was pitch two, or pitch twenty-four, I’m not sure, but suddenly there was a scream, the haul line began to stream down the wall, and then the lead rope started to go tight on the belayers. The leader was falling.

From around the corner, he appeared like a bat, a swooping fall, the rope just going tight before he hit the ledge, his feet landing on it on the rope stretch.

For a split second the belayer and leader were eye to eye, but only for a second because instead of stopping, the leader began to tip backwards off the ledge.

The belayer, acting fast, reached out just in time and grabbed his partner by his jacket, stopping him falling, and as he did so, down came one half of the lead rope, cut in half by the sharp arête above.

It’s a great story, and I’m sure it’s at least half true, the quick actions of the belayer saving his partner from a sixty-metre plunge to the end of his haul line (fingers crossed it was clipped into a full-strength belay loop, and not just the harness racking!).

This story is a scary one because it is almost heretical for climbers, as it attacks one of the necessary pillars of our climbing faith – or maybe necessary delusion – which is that ropes don’t break.

This, like all faith-based myths, is more a pragmatic than serious belief; it helps us have confidence everything will be OK as we confront that possible huge fall, or rappel off the top of a huge wall. “It will not snap, it will no break”, our subconscious climbing mantra. In some ways it’s true, they don’t snap or only snap due to extreme UV, heat or chemical contamination. But they do get cut, crushed, or ripped apart every now and then, and so it’s an issue worth actually taking notice of (and not just putting your faith in prayer!).

In my life as a climber, I’ve had one rope chewed in two by a mouse (only discovered at the base of the Eiger), three cut by falling rocks, and several that were made unusable due to disintegrating sheaths, some during falls where the rope was going over a sharp edge, but most by hauling and jumaring. There may be more, but I’ve blanked them out.

Beyond my own experiences, and without thinking too hard, or too deeply, I can think of many people I know who have also had ropes cut in the same way, including some in which the result was a ground fall.

I also know of several deaths caused by ropes cutting due to loose rock, often pulled off by the climber.

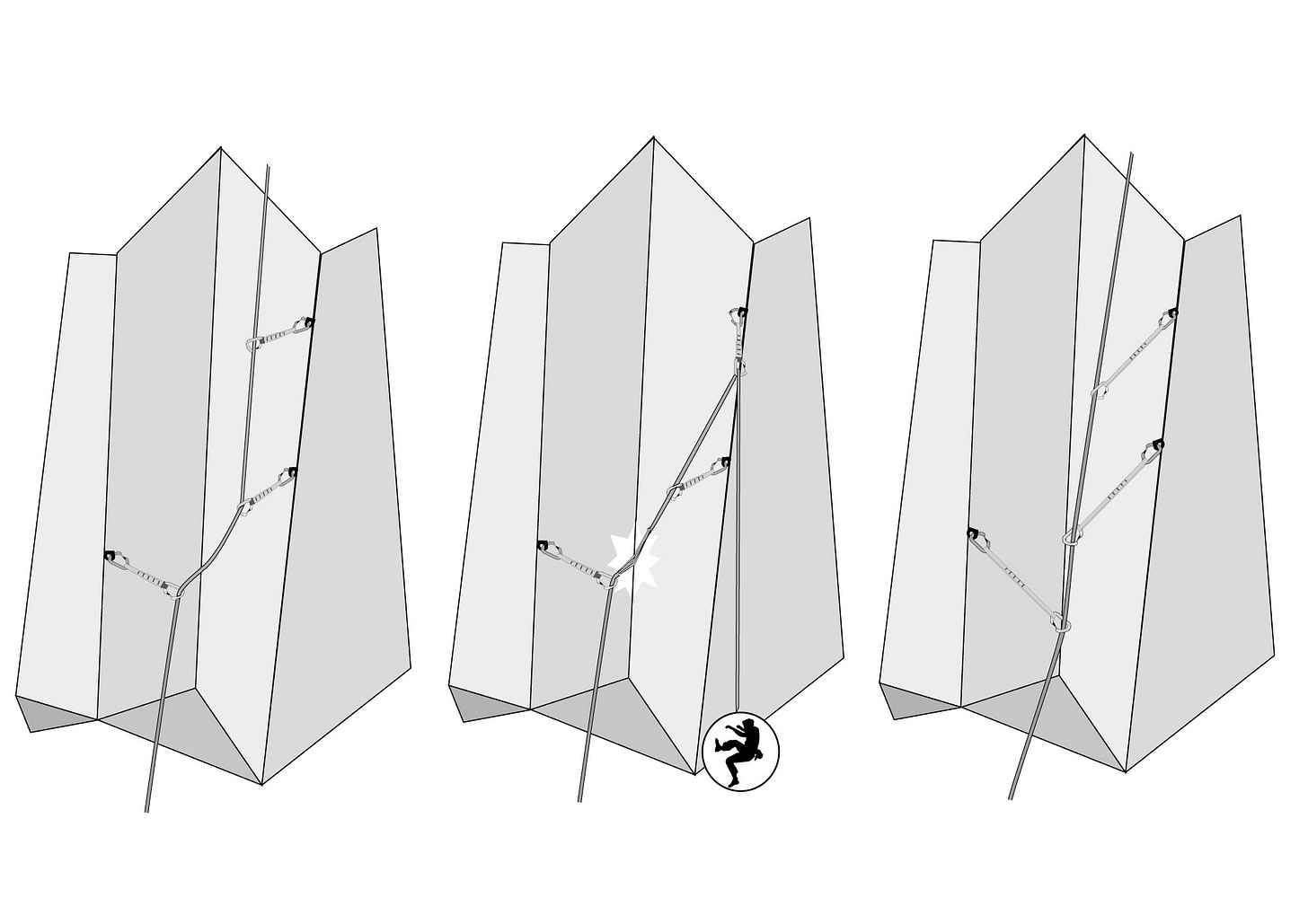

And so the two biggest factors in such damage are objects hitting the rope, and the rope being loaded over an edge, be that an arête, roof, or over a ledge.

As for snapping.

One case that was simply a rope snapping under load happened to a friend of mine, who was hauling up to the base of the Shield. They had already hauled several pitches when suddenly the haul line broke, causing the haul bags to go all the way to the bottom, luckily not killing anyone (luckily they were not space hauling). This was probably caused by the climber hauling on 9 mm accessory cord, not 9 mm semi-static rope, the fully static nature of cord versus rope just overstressing the rope fibres (they had been jumaring on the rope only that morning).

I also know someone who used a rope that had been displayed in a window for years, which broke while top-roping, and a few where chemicals had affected the rope.

So no, apart from extreme cases, ropes do not snap, but they do break.

Safety in numbers

In a perfect world, a single rope is best as it’s as close as you can get to no rope, which is what it feels like when you climb on a single strand of 8.5 mm. But in a less perfect world, a world of edges, it’s like skydiving with just one chute; it’s the best system until the day it fails.

Unlike any other part of the belay chain, a single rope is the only part of it in that failure has the highest chance of a terminal outcome. You can rip out almost every piece on a pitch, break karabiners, snap wires, crush cams, and still walk away from it. Have your only rope break and you will not.

But what are the actual chances?

Well, this depends on where and what and when you climb. A sport climber can climb every day of the week and as long as the rock is good and well bolted then there is no problem. Once you start adding in more complex and featured terrain, ledges, aretes, roofs, corners, you start to add in edges, and the rope doesn’t like edges.

Unlike a sport route where the passage of the rope will generally be uninterrupted, on more featured terrain it can take a more tortured path. The level of complexity also relates to the grade of the climb as harder routes tend to be steeper, more direct and cleaner, while easier routes are not, and will often zig-zag around in order to follow the weakness. This means that novice climbers are more exposed to dangerous features than climbers climbing at a higher grade.

Next, you add in choss, loose blocks, rubble, hanging flakes, all the crap that you can pull off, or your partner, or can just fall off on its own accord, and you have a problem. When I see some alpine God climbing a choss pitch on a skinny rope I shudder. Ropes - like people - are soft, they don’t like being struck by rocks.

So what you’re saying is...

I think most climbers should stay close to old school rope standards for standard climbing, be that indoors or out, sport or trad, winter or summer, so around 10 mm (9.5mm to 10.5 mm) for a single rope, and 8 mm ( 7.7 mm to 8.5 mm) to for double ropes, ideally dry treated.

I also think that double ropes should be viewed as the standard for trad and multi-pitch climbing, just like having two parachutes is viewed as standard. This might be harder for climbers who live in an area that has a culture of single ropes, but as soon as you start using two ropes, you will soon see all the advantages, both in ascent, descent and rescue.

Yes, skinny ropes have their place, but it’s important not to get distracted from their purpose, that they’re safety equipment, and that keeping you safe should not be compromised in any way, weight least of all unless weight is part of that safety equation. 99% of the time it isn't.

So yes, you can make the most of what rope technology has to offer, to employ a state of the art 8.5 mm single rope, or 7.7 mm half rope for your hardest climbs, but such ropes are perhaps best kept in the Bat cave until you get the call, ready for superhero business.

Great read as always

I’m wondering if the evolution of skinnier ropes has driven the gate open clearance of carabiners

Just finished a build of a small home gym and could not afford a “smith machine” (safety equipment to stop weighted bar from crushing you). So have semi static ropes hung from equalised Tnuts which I attach to the weight bar.

Only issue was all my modern carabiners ( inc DMM boas ) won’t open wide enough for a 25mm weights bar. Only one of your old wire gate aid climbing crabs fitted and a very old HMS I had saved the day

With skinny ropes come skinny open gate standards?