Thoughts on Girth Hitch Equalisation

Hi Andy, love the podcast (when’s the next one?) Also, what do you think about lark’s footing slings at belay stations? I’ve watched lots of YouTube videos but it scares me a bit as I have always used overhand knots. Do you do this?

Barry

When I first started climbing in the 80s (I did start in the 70s, but only started buying kit in the 80s), the only slings that climbers seemed to carry were Troll Super Blues, which were “1 inch” (the UK had gone metric in 1965, but continued to use British Imperial, pints, feet, pounds, etc., and still does). If you do the conversion, at 25 mm, they were only one and a half times the diameter of a 21st-century climbing sling (8 mm to 10 mm Dyneema), but they were also very, very stiff, around 2–3 mm when new, but soon got fatter with use. Strength-wise, I think they were rated as having a safe working load (SWL) of 4500 lbs, so 20 kN, but I expect testing was pretty rudimentary, the stuff you’d do in a shed, and was decades away from 3 Sigma or digital testing. The end result was these slings had a breaking strain closer to 40 kN, as demonstrated by old Troll slings (and harnesses) still passing minimum breaking strains 50 years after coming off the sewing machine.

What’s this got to do with girth-hitched equalised anchors? Well, these Troll slings, and equivalent slings made by US and European companies like Chouinard, Forrest, Edelrid, etc., had limited utility beyond being used on spikes or extending anchor points (remember, the quickdraw had yet to be invented!), as any knots tended to be bulky and stiff, and the only real anchor equalisation, if any, was done using the climbing rope(s), that is, if any equalisation was done at all. In the UK and Europe, on easy routes where a single rope was used, a lot of classic routes would have a single anchor point, like a tree, spike, or boulder, or a rat’s nest of pitons. On harder routes, where two ropes were used, you could tie off each rope to two anchor points, which was generally “good enough”, until it wasn’t. You either clipped one rope into each piece with an overhand on a bight, or clove hitch, guesstimating the correct length to achieve some kind of equalisation, or, if you wanted to be gucci, you’d clip the anchors and run the ropes back to your harness to achieve a perfect tension (but only for a perfectly directed force).

In the US, where climbers only had one rope, even on the hardest routes, you ended up with such things as “death triangles”, where all the anchor points had a single sling threaded through each one, and you just clipped into this loop (an ‘egg basket’ technique, as if the sling broke, you had nothing). Or, you made a chain anchor, with the rope clipped into the best piece, and then clove-hitched onto the next pieces one at a time. This was safer, but each piece had to take the entire load. I don’t have the figures, but I’ve always got the impression that US climbing had far more cases of death or injury from anchor failure, but these techniques are perhaps a result of a much wider use of bolts at belay anchors, something rare in Euroland.

Although climbers had slings, they tended to be 4 and 8 feet (or 60 cm and 120 cm, and before you email me, yes, some call 4-foot slings 8-foot, and 8-foot slings 16, but I never did), and didn’t use them for equalisation, as they were too thick, stiff, and not really long enough.

Even when softer and thinner nylon slings appeared on the market, from Troll, Wild Country, Edelrid and Mammut, first 22 mm, then 19 mm and finally 16 mm, each coming closer to the minimum breaking strain (going from perhaps 40 kN to 22 kN), climbers still didn’t really begin to equalise anchors with slings.

Even on big wall climbs, where forces are huge, climbers might make use of 120 cm slings between bolts with a sliding X, or two 60 cm slings, but knots would not be tied, as they would be really hard to untie.

I think one of the things that had a major impact on rope technique was the explosion in multi-pitch sport routes, where climbers switched to single ropes. Really, the quality of the anchors on modern routes means you could just connect yourself to a single bolt, and then back this up to the second; climbers began to equalise these anchors with either a sling or a bunny ears knot, the latter only used if switching leads.

How these anchors were equalised was with either a sliding X, or by adding a figure 8 or overhand knot to the sling, but seeing as we were still in the age of the nylon sling, which seemed pretty skinny compared to our old 25 mm Super Blue-style slings, people generally went for the knotted method.

By this point in the story, climbing was generally not really a game of equalisation, but more a game of redundancy, which seemed to work pretty well. You would hear stories of belays taking a factor 2 fall, and all the pieces but one ripping out, but nothing that really made people question the need to tighten everything up.

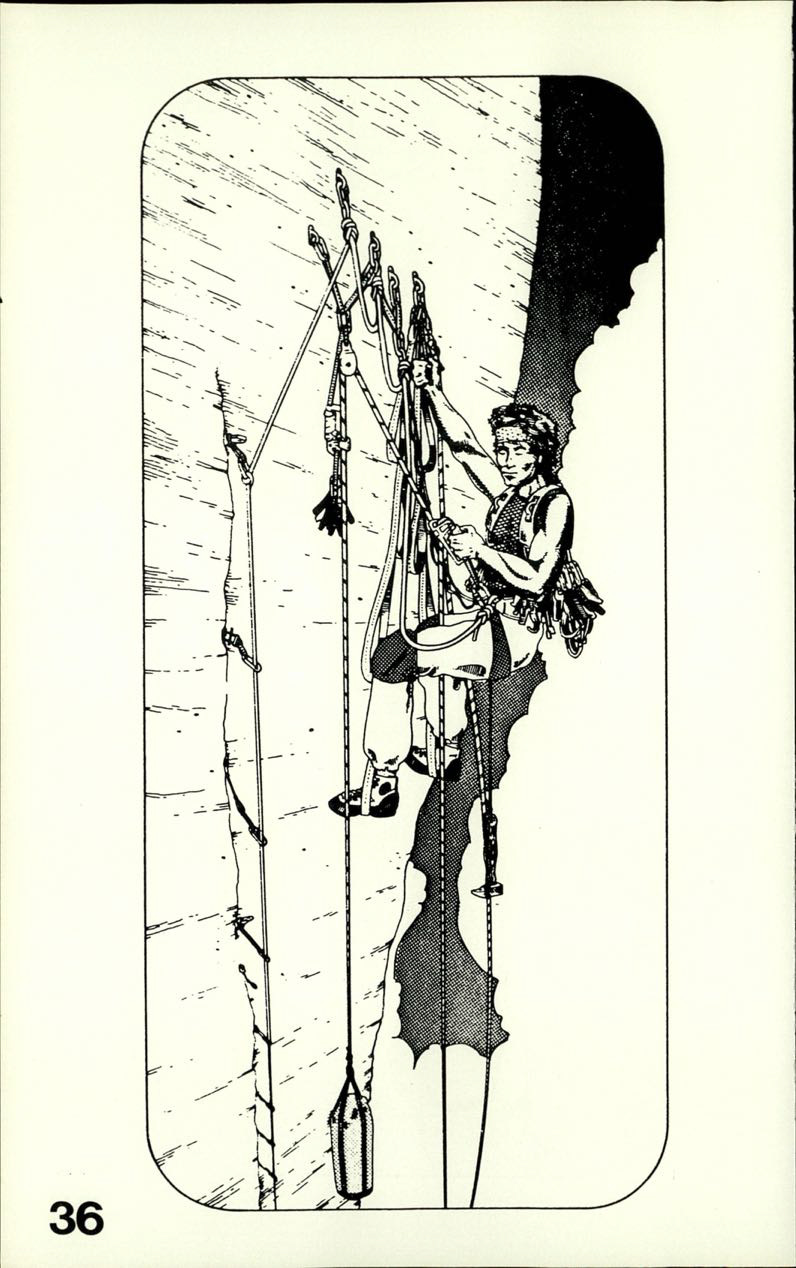

To my mind, the real change began when we started to hear whispers about this thing called a cordelette, a 5 to 7 metre length of 7 mm cord, used to link all the anchor points together, and then create a single masterpoint, where all the force could be directed out equally to each arm, like a spider clinging to a wall. Really, this tool and method is extremely specialised and focused on one type of climbing, bringing up novice climbers, fixing them to a belay, and then climbing on. The guide carries two cordelettes and rotates them from belay to belay. This length of cord can also serve to aid them in self-rescue techniques like simultaneous rappel, hauling, or rap anchors.

It’s interesting to consider the cordelette as the first Web 1.0 climbing technique, something you’d only seen in one-line descriptions in US magazines before the Web, but which overnight became the only way to belay safely, the cordelette the only way to make a solid belay anchor. The upside of this was that the technique really made people go up a gear in terms of thinking harder about making solid belays, good, when climbing was really moving from strength to strength, the rise in the average grade people climbed meaning there would be fewer spike or tree belays at the end of each pitch. Now, in the UK at least, climbers were having to construct more and more complex anchors, especially when the no-bolt ethic had to be upheld. You also had more and more climbers taking falls on all grades of routes, and although factor 2 falls remained rare, the likelihood of them rapidly increased.

It was around this time that Dyneema began to take over, going from expensive and experimental, then neck and neck with nylon, then the default. They started at a conservative (I think) 13 mm, then as people adapted to them, and “trusted the (material) science”, rapidly slimmed down to 10 mm, then 8 mm, and finally 6 mm. As the slings got thinner and lighter, they also became more knottable, and also could be much longer without a large increase in bulk and weight. For example, a 240 cm 25 mm Super Blue sling would require its own backpack, but a 6 mm Dyneema one could fit in a pocket.

These two things created a new start in belay building, the cordelette a sort of reset, using either 7 mm cord or new skinny Dyneema slings, creating a standard, but then evolving away from the cordelette, to other ways of achieving the same ends, as a cordelette is often overkill, with new ways of doing things, like the quad.

It should also be said that in this mad dash to modernity and new, better things, much of what climbers did in the past was forgotten, or thought worth forgetting, like equalising with the rope(s), chaining runners, or even trusting just two, or even one anchor point, the rule of 3, and the equalisation often leading to anchor builders having their brains scrambled, trying to tick all the boxes, like they’re being assessed by some mountain God almighty, when throwing the rope around a chockstone was all they needed to do. Maybe we need to take a page out of Ghost Dog’s book, and “stick with the ancient ways”.

Now we get to the bit about girth hitching (or lark’s footing or cow hitching slings), by which we eliminate the overhand knot used to create a masterpoint in a cordelette, equalette, or equalised sling (but not a quad, as this is designed to give you a self-adjusting masterpoint). The reason this is a relatively new thing is not that climbers in the past were backward, but that perhaps the technique had to wait for technology to catch up, that we now have slings thin enough to do this. In the past, even a state-of-the-art 13 mm Dyneema sling of the 90s would create quite a bulky knot in the crook of a locking karabiner with just a two-point anchor, let alone three or four. Even 7 mm cord gives you a much bulkier knot around the crook of the karabiner, something that may give you a stronger, more equalised matrix, but might compromise the karabiner, applying odd forces on the gate that a normal overhand does not.

I think it’s also worth considering the underlying truth of why a girth hitch is better than an overhand on a bight, that the girth hitch is easy to untie after loading, unlike an overhand. Anyone who has used the overhand method knows this isn’t really true, that even a really heavily loaded sling and cord can be easily untied by hand, yes, it might take you 20 seconds, rather than 5 seconds, but there are also advantages of the overhand method over the girth hitch, as this gives you an extra closed loop to clip into between the masterpoint and the ‘shelf’ above.

The real advantage of the girth hitch method is that it gives you marginally more control when making that final adjustment to the masterpoint knot, something that can be lost when turning the end loops into an overhand. Any slight deviation of unequalness in your sling should not be a big problem when using 7 mm cord, which is slightly dynamic, and will self-equalise, but will affect Dyneema slings, which are super static. But, if you consider how things used to be done, really, we’re moving away from the material reality of climbing and climbing theory, of possibility versus probability.

I know this is a long-winded reply, but I suppose what I’m saying is girth hitching your anchor sling or cord is the best method, as are all the others. Perhaps at X belay, a girth-hitched sling off two bolts will not only give you the most effectively equalised belay, but also a belay of equal strength, simplicity and speed. Using a 7 mm cordelette could well give you a stronger belay, but it will not be as simple, or fast to build or take apart. You could just use your ropes, which would be the strongest, simplest and most dynamic method, but if you need to swap ends with your partner, you’ll lose points.

So, there is no single “way” to do anything, rather, it’s about mastering (or at least understanding) as many ways as possible, so you can apply the method you, and your partner(s), feel most comfortable using.