I watched a great video the other day of two climbers space hauling (HowNotToHighine see below), a method of lifting very loads with just a simple 1:1 haul, e.g: just a single pulley, where one climber hauls and the other acts as a counterbalance.

Such a heavy load could be lifted with a 2:1 or 3:1 or greater (the Petzl Jag allows you to do a 4:1 or 5:1, making it ideal for 4 person teams on multi-week walls), but each time you increase the ratio you also increase the time, so a space haul is always the fasted method of lifting a big load (you might be on a wall for several days, or weeks, but speed is always vital when you have finite supplies).

In the video, I noticed a few things worth critiquing, not to slander anyone (the methods used are appropriate), but to kick of the subject of advanced hauling and staying alive on a big wall.

Safety first or fifth?

First of all, when it comes to climbing safety, you can either take a sort-term, speedier, “sketch-ball”, ‘safety fifth’ approach or a longer-term, long-game, paranoid approach. Sometimes your safety requires you to be unsafe, because speed is the key to staying alive, while other times you need to adopt a level of by the book caution you’d only find demonstrated by a bomb disposal expert. Each state of caution is appropriate for its appropriate circumstance, and sometimes a single route or even a single pitch might require a climber to switch between both states, or even somehow inhabit both at the same time! But neither state is one in which safe or effective climbers can inhabit all the time, and so most climbers tend to adopt a “safety second” or “third” mindset (the optimistic pessimist/pessimistic optimist).

“Sketch-ball” Space Hauling

In the “Safety fifth” approach, you trust all your gear without question, that all pulleys are strong, all karabiners solid (done up, inline and not cross-loaded), and all systems perfect, ropes unbreakable, not to mention all members of your team (and yourself) immune from human error.

Here you will not bother backing up your pulley, or give the dead weight counterbalanced climber a back-up rope, meaning the climber just clips their ascenders into the haul line and hangs from the pulley as the other climber hauls, and down they go. Doing it this way reduces the tangle of having a second safety line, keeping everything clean, and does away with extra and annoying lockers clipped into the rope in case of pulley failure. 99.99% of the time this is safe, fast and effective, as long as everyone is 100% solid at hauling, rigging, climbing ropes, and communicating with each other. If not, then those odds will not be so good.

What is the chance of such a catastrophic failure?

Well, I know of one climber who had his haul line break while hauling on the very same pitches in the video, the line breaking as it passed over the edge of a ledge (see video at 17:54), which sent his bags to the bottom of El Cap. The cause of the broken rope was never really identified, although I suspect he was using 60 metres of 9 mm accessory cord, not actual static rope, which is not actually as static as accessory rope (the rope was yellow, which at the time was the colour of Marlow 9 mm cord). It goes without saying that if his partner had been space hauling he’d have died.

I’ve also had a lot of experience with rockfall while hauling, the causes of which have been both natural as well as man-made, rocks knocked off the ledge while hauling, haul bags dislodging flakes, or a cleaner knocking off rocks as they climb. Any rock of even medium size, hitting a loaded haul line will probably cut it like a knife. If you don’t believe me, try hanging two people on a length of old rope sometime and see how easy the rope cuts while being loaded (you can easily slice through it with just a shoelace, which is why you should always be paranoid about haul lines moving close to fixed lines).

Another paranoia point is to also be scrupulous about rope management when hauling, and make sure the rope you’re clipping into to space haul is the correct rope, and in the correct orientation. The idea of clipping into the end of a haul line, so you just fall to your death, might sound stupid, but when it’s 1 am, and you’ve had nothing to eat or drink all die, and just want the day to end, well… it can end all too easily. Personally, when on a wall, I try and avoid end ropes ends being left free, meaning all unused ropes are in bags, tied up, and all rope ends clipped in.

Then you have the problem of your bags coming detached from the haul line. This can happen in all sorts of ways, from an incorrectly tied knot (such as an incorrectly tied Alpine butterfly), or cross-loading a karabiner between loaded suspension straps, or simple ultimate pilot error, where the bags are not attached to the haul line at all or are attached to a non-load bearing part of the bag.

And then you have the pulley end. Yes pulleys, by their nature are incredibly strong, but they do fail, generally due to being used incorrectly. Pilot-error includes not locking closed a two-part pulley (like the Pro Traxion), leading to it opening under load, having the pulley upside down (a classic Pro Traxion error), or simply overloading the cam (I’ve seen the old Rock Exotica Wall Hauler deform under huge loads).

In any haul system, you also have the issue of the cam in the system, a method of rope breaking that works by using the load itself to compress – or crush – the rope. The greater the load on the rope, the greater the load pass through the cam into the rope. This is why no ascender or cam should be exposed to any loading above 4kN (407 kg), as doing so will first strip the sheath from the rope, and then cut the rope itself. What are the chances of a 4kN load? Well on a long wall, with a team of three, carrying a lot of water, food, ledges, rack etc, I think you could easily hit 200 kg. Have such a heavy load swinging around, or get jammed, and extra pressure put onto the line, and you could generate these kinds of forces. Then you’ve got all those apocalypses events, like your bags picking up a 200 kg flake or a dead tree (it happens) as they rise up, or get caught by an avalanche, or end up inside a waterfall, or swung around in a wind storm.

You also have classic “oh shit” events, problems you see or predict when under stress, such as a friend who was counter hauling their bag, only to find the bag, once the bag cleared a few friction points, was much lighter than them, causing them to plummet down the wall until the bag hit the belay!

The consequences of a failure of the system depend on what fails, and in some situations, you might be saved by a knot jamming into the hauling device, or the climber who is hauling might catch the moving line in their ascenders as they flip and reverse...maybe. But if someone breaks, what happens next will be instant, and with massive forces in play, the outcome will probably not be good.

In all such situations, losing just your haul bags would be a catastrophic incident, but not a tragic one. Losing your bags and your counterbalanced climber would be.

Paranoid approach

The alternative method is to never really trust any piece of the safety chain, or anyone, even yourself, to always listen to your nagging paranoia. This does not mean you’re a safety-first kind of person, but not safety-fifth either.

With this approach, you will try to avoid trusting anyone’s life to a single piece of equipment, which in this case is the rope, unless it is unavoidable (this is why so many climbers die rappelling). Instead of just hanging from the haul line like a deadweight (without the weight of the bag, you’d be dead), the counterbalanced climber always remains tied into a section of rope - ideally dynamic lead rope - which is clipped into the belay, ideally not into the actual masterpoint into which the hauling device is clipped.

The job of the hauler should not only be to haul, but also to be the brake person, watching out for an imbalance rope and control the speed with their gloved hands (near the top of a wall, if you continue to space haul, you will not need an ascender, and can just pull the rope through the pulley by hand).

This safety rope will come tight after a certain distance, generally around 10 or 20 metres at which point the climber re-ascends the haul line and starts again. This may sound like a pain, but it tends to stop the counterbalanced climber from getting exhausted as they keep re-ascending the rope (on overhanging pitches it can knackering), and gives the hauling climber a break as well.

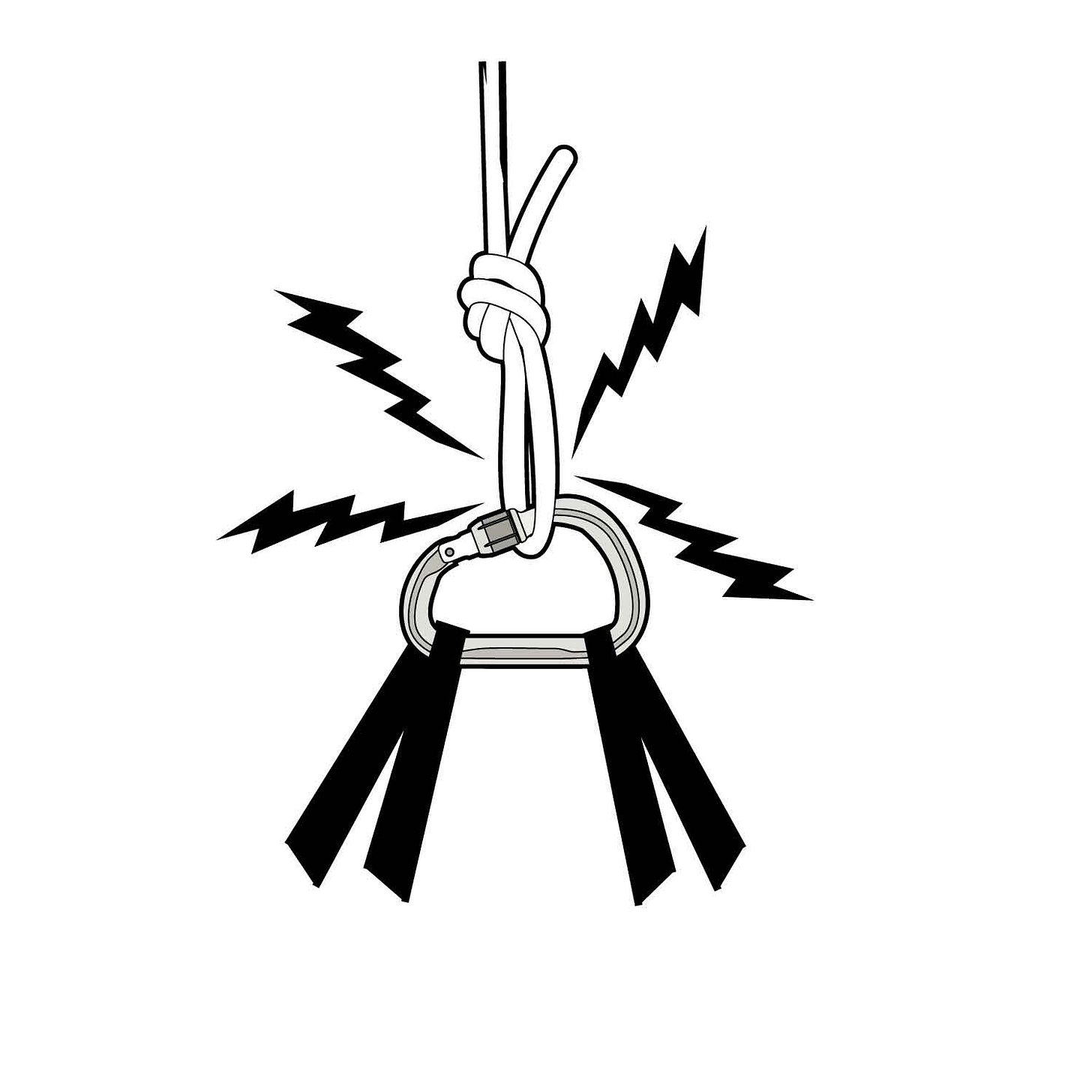

Next, you want to have your pulley backed up. This means first of all you have to be diligent in making sure it’s set correctly and locked in place. Use a karabiner to keep the hauler locked together (clipped into the bottom of your Pro Traxion), and also clip a draw (ideally a locking draw) from the masterpoint to the rope.

Next, you want to always have a 100% secure method of connecting your haul line to your bags. This can be done in many ways, but I would either use two hard links (two lockers), or 10 mm hard link, or even tie the line to the bags with a backed-up bowline. It’s the duty of the last person on the belay, who releases the bags, to make sure there is no cross-loading, but sometimes it’s unavoidable on a crazy lower out. As a rule, the bags should never be undocked until they have been fully lifted off the belay, and the last person can check everything is loading correctly, and that all your bags aren’t being held by the gate of a cross-loaded karabiner. Yes, the knot would eventually hit the hauler, but if that means your counterweight falls 60 metres down the cliff, bouncing off ledges, it won’t do them any good!

In part two I’ll discuss an alternative to space hauling for heavy loads.

Part 2 coming soon?

Funny I just watched this video last week. The space hauling looked very fast, almost unbelievable that he could haul that much on a 1:1. Question - would space hauling be useful for low angle routes with a lot of obstacles (like first 2 pitches on Washington Column, or is it better just to have the second mind the bags?